- Home

- Photo Galleries

- Portrait Photography

- Landscape Photography

- Street Photography

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Holy Ganges

- Varanasi

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti

- Varanasi, Manikarnika Ghat

- Varanasi Streets & Alleys

- Varanasi Demolition

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- Sarnath

- Brick Kilns

- Tamil Nadu, Chennai & Mamallapuram

- Tamil Nadu, Fort Tirumayam & Madurai

- Tamil Nadu, Tiruvannamalai & Thanjavur

- Kerala, Munnar

- Kerala, Peryiar

- Kerala, Backwaters

- Kerala, Kochi

- Kazakhstan

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Travel Blog

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Tamil Nadu & Kerala

- Varanasi

- Whato to do in Varanasi

- Varanasi Life along the Ghats

- Varanasi Death along the Ghats

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti Ceremony

- Varanasi demolished to honor Shiva

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- “Varanasi, A Journey into the Infinite”

- Sarnath

- All about River Ganges

- Holy Shit. All about Indian Cow Dung

- Clean India Project

- Brick factories

- Tilaka, pundra, bindi: what is the mark on Indian foreheads?

- Kazakhstan

- Mongolia

- Ulaanbaatar, the coldest capital in the world

- What to do in Ulaanbaatar

- Chinggis Khan Museum, 6 floors of Mongolian history

- Gorkhi-Terelj National Park and Bodgkhan Natural Reserve

- Altai Mountains, Things to do in Olgii and Sagsai

- Living with the Eagle Hunters

- Sagsai Eagle Festival

- Navrus Festival

- Xöömej, Mongolian throat singing

- Mongolian Food

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Latest Posts

- Photography Blog

- About

- Prints

“Money! Money Money!” Dusty little hands searching my pockets for candy and pens and I curse that I haven’t brought enough for everyone.

Share with your friends:

Harar, UNESCO World Heritage

Ethiopia. Harar is a historic town, the fourth largest in the Muslim world. Situated in a strategic position, Harar has been a trade hub from ancient times. Today, the city has 250,000 inhabitants. With its 82 mosques, six gateways and colourful labyrinthine alleys, it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Harar is well known fot its exquisite coffee, but most people know it was the place poet Rimbaud chose to spend the latest days of his life.

The city is also famous for a peculiar tradition. At night, a man goes outside the city walls and mouth-feeds hyenas. There is indeed a very special friendship between men and hyenas in Harar. Feeding them protected the people who live here and their cattle from being attacked.

We cross Harar’s city walls after crossing tirelessly the Danakil desert. We slept by the side of the road, with stray mules that smelled our hair out of curiosity. When the sun got too hot, we asked for a shelter in strangers’ barracks. We suffered from the extreme weather conditions in the region and we felt very fragile. At night, when only the moon was shining, in timeless silence, we felt alive and vital. We now enter the city by one of its six gates: we return to civilization after being stripped of centuries of progress.

Maybe we really traveled in time, because the city has all the charm that it had to have in the 600s, when it was founded. Without the Coca-Cola logo, which dominates store walls almost everywhere, suspicion would be more than justified.

Children in Harar

Every alley teems with children: they run towards us without fear, free from education. “Money! Money! Money!” They rush towards you as fastas they can, and before you can see them, they’re checking what’s inside your pockets. “Money” is the only English word they know. In fact, they don’t want money but just any gift: candy, pens, notebooks.

When a dusty hand gropes at you like that, you curse yourself for not bringing baskets of mints and pencils. Photographing them is a physical experience, too. As soon as they hear the click, they pull down your camera and hit the buttons with their fingertips to see themselves on screen. And they’re all laughs and winks. Older children ask you to play, they take out a sponge ball and test your bagher.

Trade in Harar

Intertwined with the world of children and sharing spaces seamlessly, there is the adult trade. At the market you can buy wheat, coffee, spices. Everything is in the beans and leaves, still to grind at the mill. The air is fragrant but so dusty it is hard to breathe.

Butchers are built out of bricks. I think it’s one of the most lucrative businesses, because women linger to chat with the butcher and try to flatter him giggling. When I approach him to take some pictures he’s not as kind to me. I better not photograph him or the meat he sells. Barbers and hairdressers are a lot nicer: I ask them to cut my bald friend’s hair and we all laugh as old friends!

Typical houses in Harar

Our guide shows us the typical houses. The first space you get to crossing the street, is the courtyard. The houses are designed to keep the cool air inside, so the main hall is built on several different levels, such as steps in a staircase.

The higher step is up to the head of the family, the intermediate one to the wife. Then, descending of importance, come the stairs reserved for children, guests, servants. Many hats hang on the walls. It takes many hours for each one to be woven and each one is there to celebrate a special occasion worth remembering. For example, You make (or purchase) a hat when you get married, when children are born, when they get married or graduate. Every hat on the wall of a house is there like a page in the family’s history.

The host is very shy. She doesn’t want to be photographed and doesn’t talk to us. But when it comes to hanging up, she doesn’t back down and I can catch her fleetingly.

Chewing qat (aka chaat)

Outside the city walls, people gather bundles of sticks and sell the famous qat (or chaat). It is a plant whose leaves they chew to avoid feeling tired from work. Legend has it that qat was born from a drop of the life elixir. They’ve been growing it massively since the ’90s, when coffee production has dropped. Everyone seems to love it and they talk about it with a cheeky smile on their face. They want me to try it and make fun of me when I decline.

Rimbaud's House & Museum in Harar

The sky is clouded and it starts to rain. We hardly believe it as we head towards the house of Rimbaud, which has been turned into a museum. The majestic facade and the large wooden loft with stained glass are very suggestive – but false.

The whole structure was built after Rimbaud’s death on the same site of his real home, which had to be much more modest. Rimbaud liked to live here but could not run a successful business and began to abuse qat. Eventually, he had to leave Harar and return to Europe due to a cancerous leg infection. He died yearning to return.

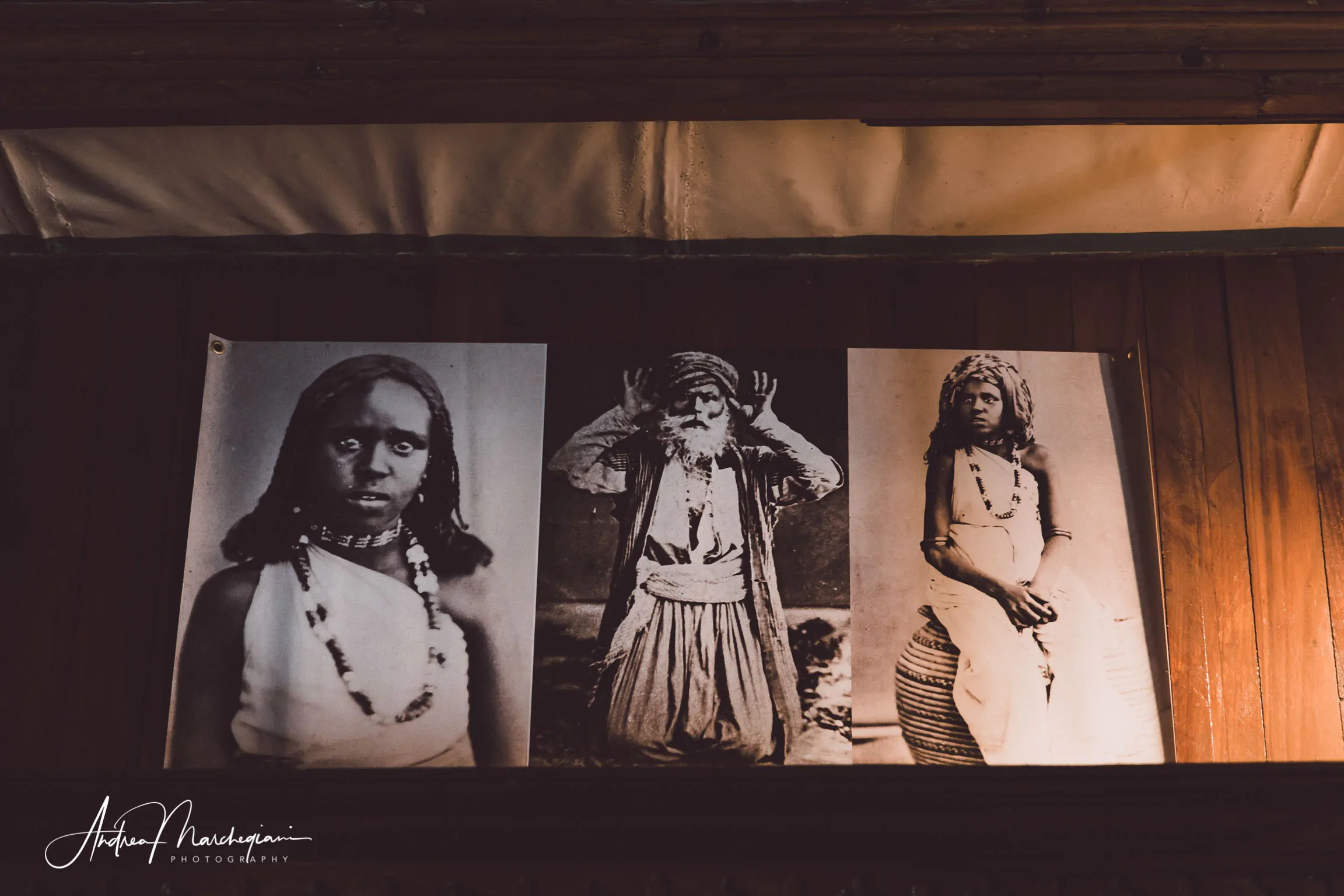

The museum presents a captivating photographic exhibition that testifies to the reality of Harar at the time of Rimbaud, at the end of 1800. I look at the photos with the melancholy that the poet had to feel leaving Ethiopia.