- Home

- Photo Galleries

- Portrait Photography

- Landscape Photography

- Street Photography

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Holy Ganges

- Varanasi

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti

- Varanasi, Manikarnika Ghat

- Varanasi Streets & Alleys

- Varanasi Demolition

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- Sarnath

- Brick Kilns

- Tamil Nadu, Chennai & Mamallapuram

- Tamil Nadu, Fort Tirumayam & Madurai

- Tamil Nadu, Tiruvannamalai & Thanjavur

- Kerala, Munnar

- Kerala, Peryiar

- Kerala, Backwaters

- Kerala, Kochi

- Kazakhstan

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Travel Blog

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Tamil Nadu & Kerala

- Varanasi

- Whato to do in Varanasi

- Varanasi Life along the Ghats

- Varanasi Death along the Ghats

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti Ceremony

- Varanasi demolished to honor Shiva

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- “Varanasi, A Journey into the Infinite”

- Sarnath

- All about River Ganges

- Holy Shit. All about Indian Cow Dung

- Clean India Project

- Brick factories

- Tilaka, pundra, bindi: what is the mark on Indian foreheads?

- Kazakhstan

- Mongolia

- Ulaanbaatar, the coldest capital in the world

- What to do in Ulaanbaatar

- Chinggis Khan Museum, 6 floors of Mongolian history

- Gorkhi-Terelj National Park and Bodgkhan Natural Reserve

- Altai Mountains, Things to do in Olgii and Sagsai

- Living with the Eagle Hunters

- Sagsai Eagle Festival

- Navrus Festival

- Xöömej, Mongolian throat singing

- Mongolian Food

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Latest Posts

- Photography Blog

- About

- Prints

“Abreha We Atsbeha church is beautiful indeed! It will be full of fleas and ticks, though.”

Share with your friends:

When setting off on a new journey, the first thing to scrape away are our habits. We remember ourselves as being wild wanderers when we came back from our last trip and we still like to think we are that way, while in fact just a few months inside our comfy house have turned us back into what we most loathe. Tourists. Westerners. Hyper-clean lovers of comfort.

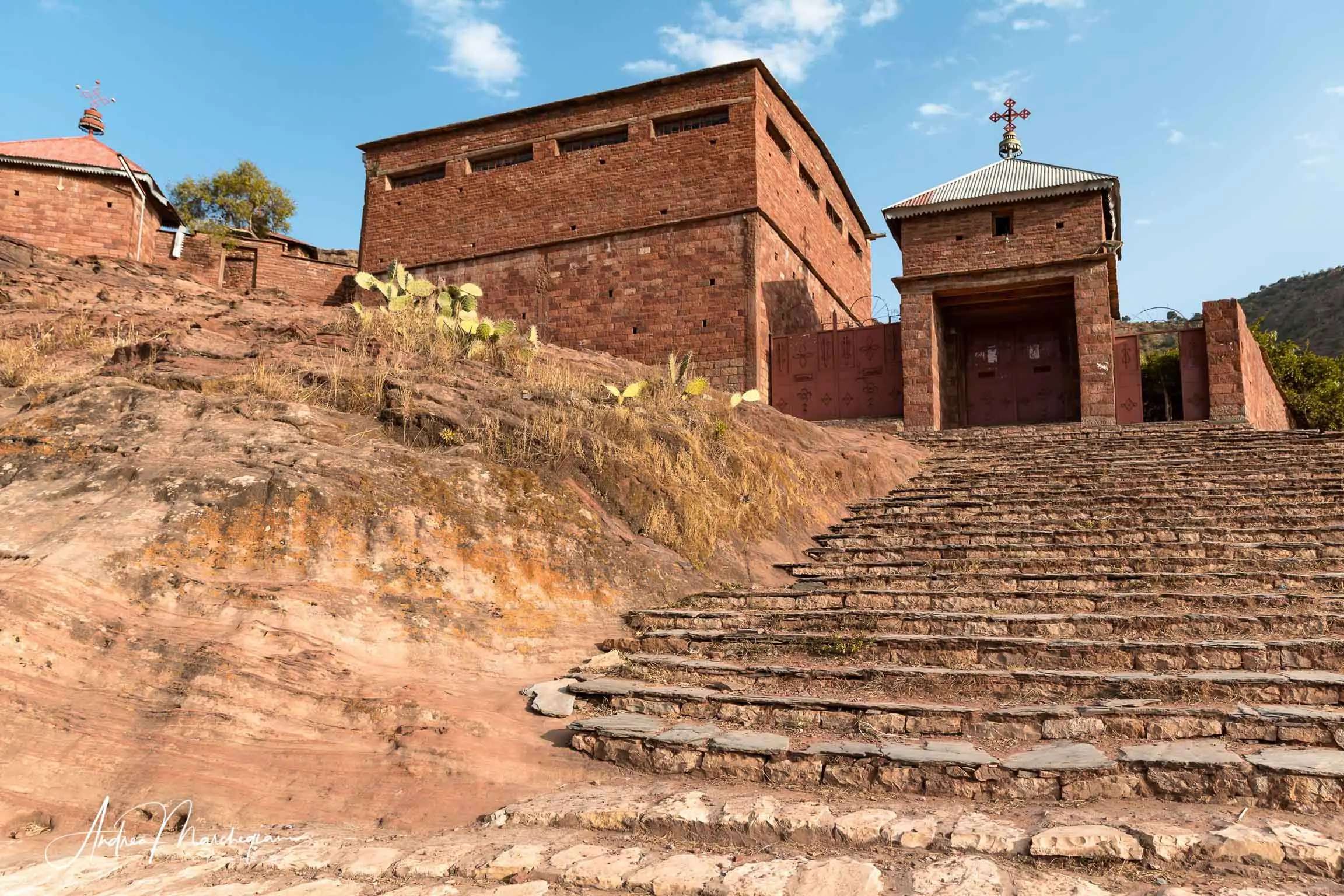

I have arrived here in Ethiopia just a few hours ago and I’m about to visit the first destination of my trip, Abreha we Atsbeha church. Built in the 10th century, it was named after the two kings who converted Ethiopia to Christianity.

The building is semi-monolithic: partially carved out of rock, partially built in masonry. It is located in the Tigray region, which is in the extreme north of Ethiopia. The population here is Coptic and built many monolithic churches throughout the area which became well-known for their architectural style and the fascinating rites celebratred there during religious holidays.

The church of Abreha we Atsbeha is less known than those in Lalibela, but just as fascinating. Located a few kilometers from Wukro, at an altitude of 2200 m, it overlooks a small plateau with an enchanting view.

A priest awaits us at the entrance door, which is still closed. Almost a single block of wood, very heavy, carved by time and burned by the sun. Without showing the slightest interest in us, the man opens the door and enters. I’m sure he does that gesture exactly the same way when he’s alone. His face and detached manner exude an unparalleled charm.

Inside, the church is entirely painted with scenes representing events from Ethiopian Christian history. Downstairs, a pile of dusty rugs decorate the rough floor. We have to take off our shoes to enter.

“It looks stunning indeed. But it must be full of fleas and ticks.”

I hear the passing comment as I take off my shoes and wipe the sweat from my neck.

Someone starts spraying their ankles with repellent, hoping it will help; someone else has already made it clear that they will come in wearing old socks just to throw them away as soon as the visit is over.

“I really don’t understand this thing”, a friend whispers annoyed, “why does someone have to take off their shoes in sacred places!”

We survived a complicated flight plan and we slept 40 minutes in the last 36 hours. The SPF 50 sunscreen has melted with sweat and is now dripping down our foreheads into our eyes, which are already hurting from lack of sleep. At the mere suspicion of fleas, we started scratching our arms and legs.

Badly concealing our fear, we enter barefoot and itchy. The frescoes are from the 16th century and fill the view with bright colors.

The carpets are placed untidily, the dust thickens the air, infiltrations endanger the wooden roof and the paintings – every detail suggests the church is in a state of abandonment. We comment on the criminal standards of maintenance of such a work of art, when we glimpse the priest sitting on the sidelines waiting for our visit to end. We fall silent. The afternoon light enters through the side door, with a glimpse of the surrounding countryside, and is reflected on the drapes of his tunic. It looks like a mystical apparition.

We enjoy the moment, embracing every nuance. We smell the air, we explore every shadowy niche with our eyes, we admire the beautiful face of the priest, his unreachable and intense eyes, we try to guess what mysterious thoughts they hide.

It’s a kind of baptism. We enter Abreha we Atsbeha as tourists and leave as travelers. Nobody talked about dirty socks anymore. With all due respect to imaginary fleas.