- Home

- Photo Galleries

- Portrait Photography

- Landscape Photography

- Street Photography

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Holy Ganges

- Varanasi

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti

- Varanasi, Manikarnika Ghat

- Varanasi Streets & Alleys

- Varanasi Demolition

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- Sarnath

- Brick Kilns

- Tamil Nadu, Chennai & Mamallapuram

- Tamil Nadu, Fort Tirumayam & Madurai

- Tamil Nadu, Tiruvannamalai & Thanjavur

- Kerala, Munnar

- Kerala, Peryiar

- Kerala, Backwaters

- Kerala, Kochi

- Kazakhstan

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Travel Blog

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Tamil Nadu & Kerala

- Varanasi

- Whato to do in Varanasi

- Varanasi Life along the Ghats

- Varanasi Death along the Ghats

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti Ceremony

- Varanasi demolished to honor Shiva

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- “Varanasi, A Journey into the Infinite”

- Sarnath

- All about River Ganges

- Holy Shit. All about Indian Cow Dung

- Clean India Project

- Brick factories

- Tilaka, pundra, bindi: what is the mark on Indian foreheads?

- Kazakhstan

- Mongolia

- Ulaanbaatar, the coldest capital in the world

- What to do in Ulaanbaatar

- Chinggis Khan Museum, 6 floors of Mongolian history

- Gorkhi-Terelj National Park and Bodgkhan Natural Reserve

- Altai Mountains, Things to do in Olgii and Sagsai

- Living with the Eagle Hunters

- Sagsai Eagle Festival

- Navrus Festival

- Xöömej, Mongolian throat singing

- Mongolian Food

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Latest Posts

- Photography Blog

- About

- Prints

“I found these paintings rolled up under the beds of old widows, buried in the family trash, in dark corners of art studios, sometimes used as patches for roof holes. The result was a collection that no one in the Soviet Union would dare to show.”

– Igor Savitsky

Share with your friends:

Igor Savitsky, The strength of the individual

In times of adversity, when all seems lost, history teaches there is always someone who does not give up and keeps on fighting, in spite of all evidence. People like that become an inspiration, and sometimes their efforts really make a difference. As happened in Uzbekistan, in Nukus, a town forgotten by the world. Here a man alone has defeated one of the most ruthless censorship campaigns in history.

Nukus – the Aral Sea and the Karakalpakstan Art Museum

Two things turned Nukus into the isolated capital of the Karakalpakstan region. The first is its proximity to the Aral Sea, an ancient sea today almost completely drained by Soviet madness. On its polluted sands, which the sun dries up, rises today an anguishing Memorial Museum. The second is the Karakalpakstan Art Museum, with its 80,000 works of art, which is the world’s second largest collection of Russian avant-garde paintings from the 1920s to 1930s.

In both cases, Nukus shows us that nothing is impossible. There is no limit to human madness, in the case of the Aral Sea, nor to the courage and value of individuals, as evidenced by the work of Igor Savitsky.

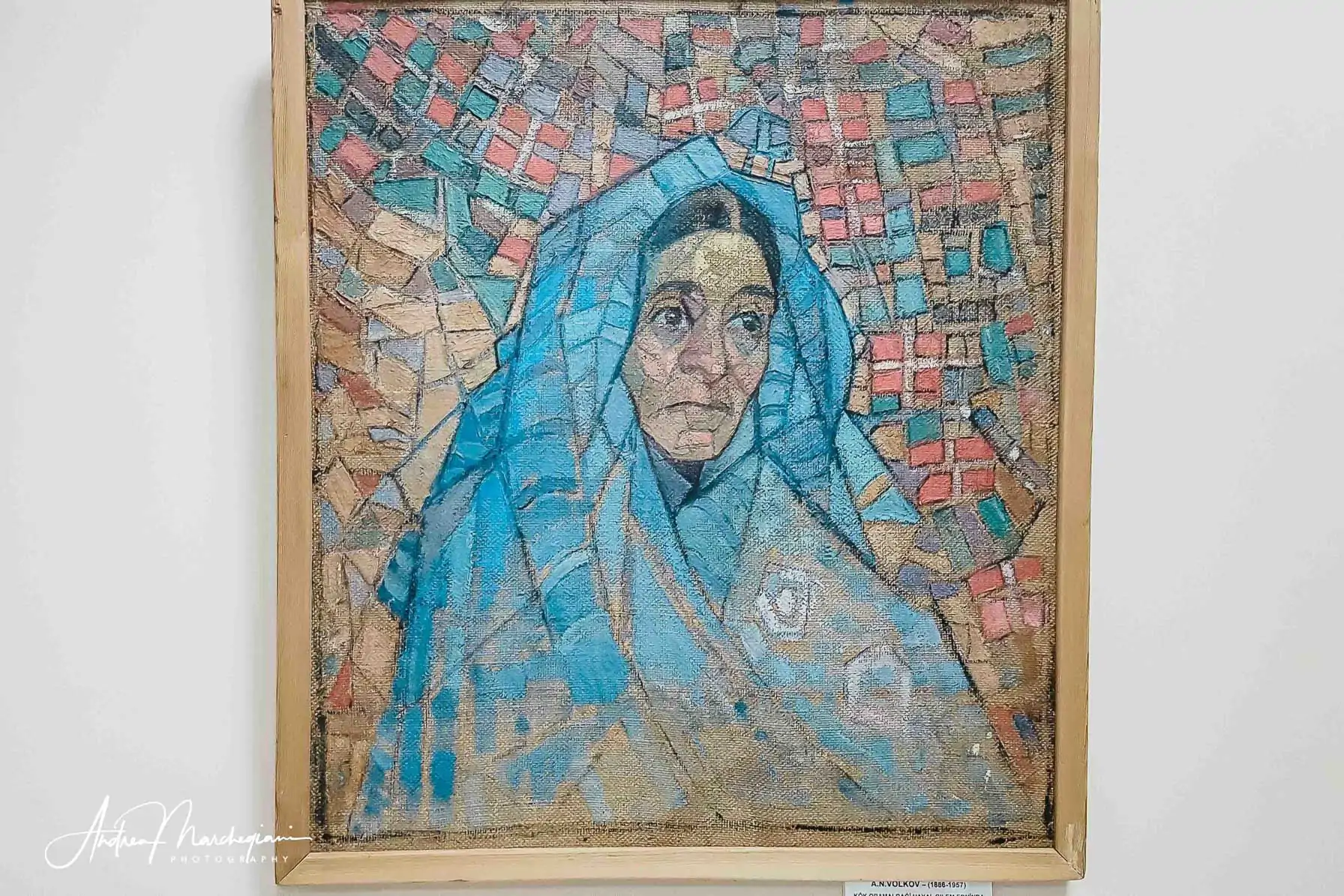

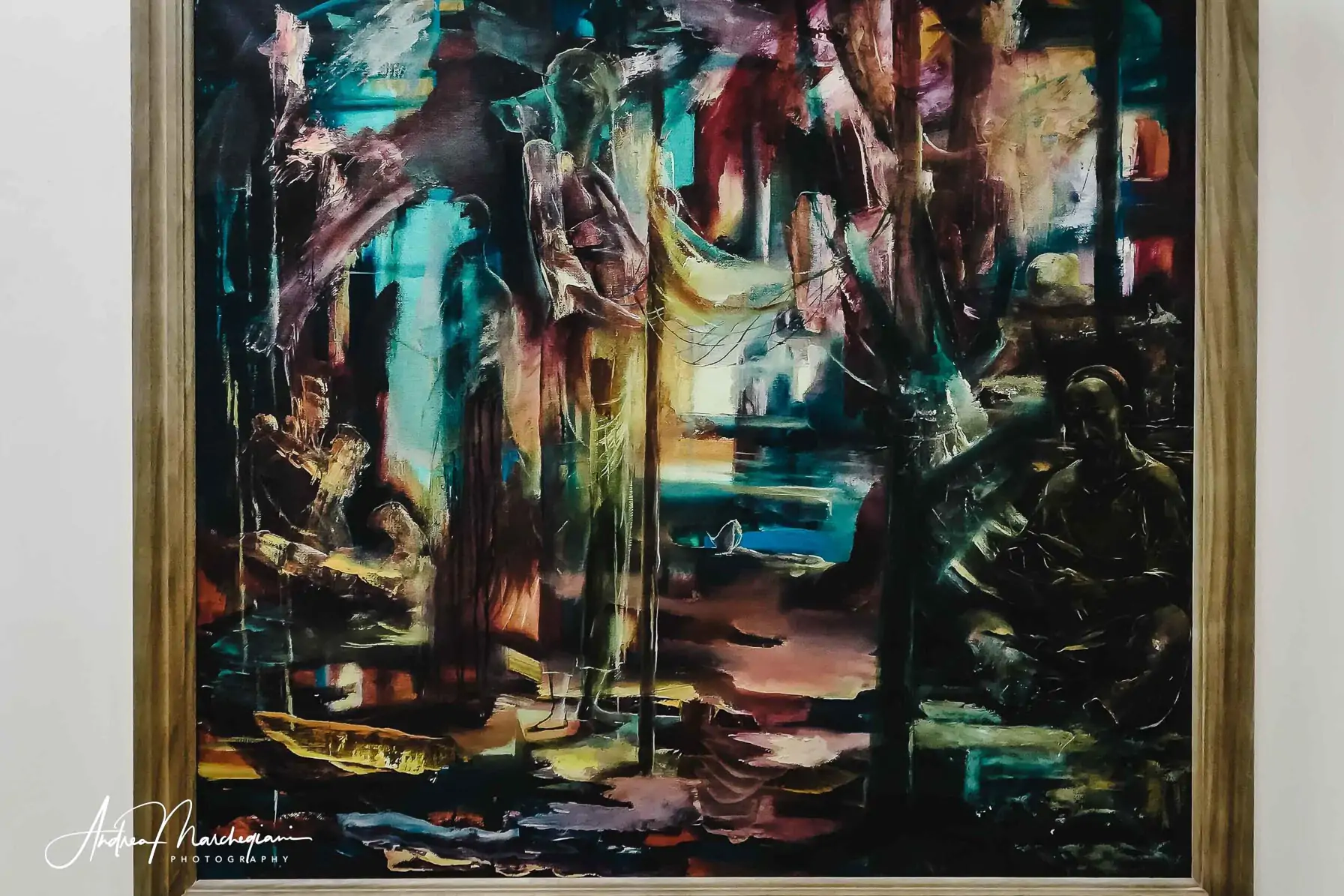

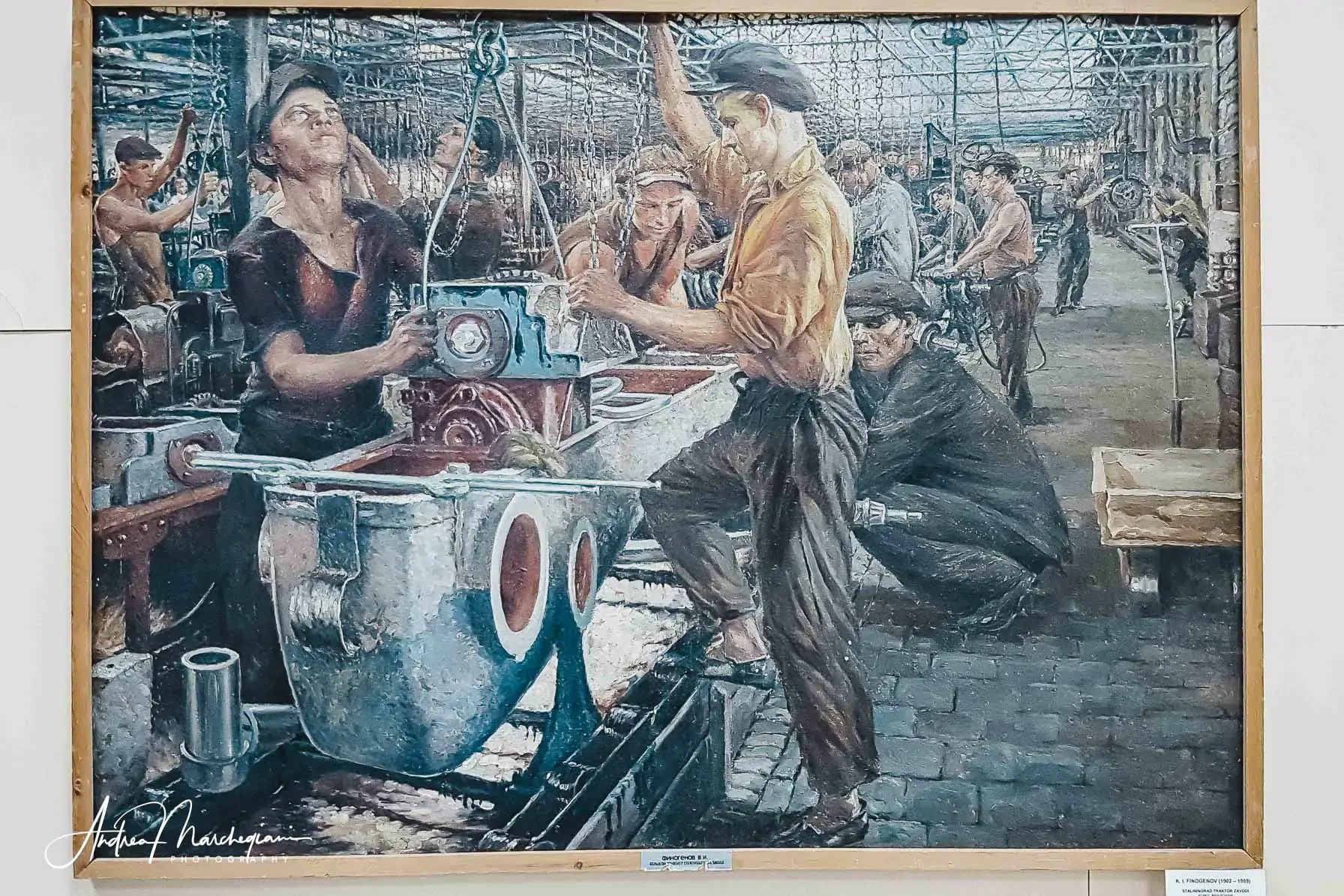

Stalinist purges

Socialist Realism was born in 1932, with forms and contents rigidly codified by the Regime and published in an edict. Artists who refused to conform to the established aesthetics were arrested, confined or murdered. The great Stalinist purges claimed victims not only among the leaders of the party, but also among intellectuals, journalists and painters. Yet some free voice resisted and expressed itself in the shadows. It has come to this day thanks to people like Igor Savitsky, who have collected and preserved works of art as dangerous as unexploded mines.

Igor Savitsky

Passionate artist and professional archeologist, Savitski arrived in Nukus in 1950, following an expedition by the Soviet Cultural Superintendence. He fell in love with Central Asian culture and settled in the town. Ten years later, he opened a local art museum which was recognized by the authorities in 1966. In addition to collecting works of local ethnography, Savitsky began to collect the production of artists belonging to currents condemned by the Regime, works that he should have denounced and burnt.

“In here”, explains Marina Babanazarova, the first curator of the museum, “there are more than 80,000 works, mostly linked to the Russian avant-garde: in particular, those ranging from the 1920s to the 1940s. Igor Savitsky received them directly from the authors, many bought them from families or were entrusted to him in secret to keep them to safe”.

In the basement of the museum, unbeknownst to the regime, Savitsky amassed thousands of works by artists deported to the gulags. Many are still piled up where Savitsky left them and waiting for funds to find a proper location. Not all are masterpieces by great authors, but some could even rewrite the history of modern art, open new intellectual paths, reveal new influences.

I walk the streets of Nukus, regular and anonymous as the Soviet style dictates. Not even the sunny and summer day can defeat its greyness. But I’m glad I added Nukus as a stage in my trip to Uzbekistan: as soon as you enter the doors of the museum, the geometries and colors of the paintings explode with life and emotions. I observe with respect every work, I dedicate a moment of admiration to it. I reflect on a not too distant time when painting freely was dangerous. Every hanging work was a cry for revolution and this makes them all masterpiesces of inestimable value.