- Home

- Photo Galleries

- Portrait Photography

- Landscape Photography

- Street Photography

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Holy Ganges

- Varanasi

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti

- Varanasi, Manikarnika Ghat

- Varanasi Streets & Alleys

- Varanasi Demolition

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- Sarnath

- Brick Kilns

- Tamil Nadu, Chennai & Mamallapuram

- Tamil Nadu, Fort Tirumayam & Madurai

- Tamil Nadu, Tiruvannamalai & Thanjavur

- Kerala, Munnar

- Kerala, Peryiar

- Kerala, Backwaters

- Kerala, Kochi

- Kazakhstan

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Travel Blog

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Tamil Nadu & Kerala

- Varanasi

- Whato to do in Varanasi

- Varanasi Life along the Ghats

- Varanasi Death along the Ghats

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti Ceremony

- Varanasi demolished to honor Shiva

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- “Varanasi, A Journey into the Infinite”

- Sarnath

- All about River Ganges

- Holy Shit. All about Indian Cow Dung

- Clean India Project

- Brick factories

- Tilaka, pundra, bindi: what is the mark on Indian foreheads?

- Kazakhstan

- Mongolia

- Ulaanbaatar, the coldest capital in the world

- What to do in Ulaanbaatar

- Chinggis Khan Museum, 6 floors of Mongolian history

- Gorkhi-Terelj National Park and Bodgkhan Natural Reserve

- Altai Mountains, Things to do in Olgii and Sagsai

- Living with the Eagle Hunters

- Sagsai Eagle Festival

- Navrus Festival

- Xöömej, Mongolian throat singing

- Mongolian Food

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Latest Posts

- Photography Blog

- About

- Prints

With my mind full of the picturesque views of Khiva, I keep traveling along the ancient Silk Road and arrive in Bukhara. In my opinion, here is the most fascinating artistic heritage of all Central Asia. In fact, Bukhara suffered a less invasive restoration than Samarkand and still resembles what Turkestan looked like before the Russians conquered this land. I stay here two days, walking along the alleys and crossing the covered markets. Every time I look up, I marvel at the facades of the madrassas and the profiles of the minarets, which seem to enjoy being admired.

It’s love at first sight.

Share with your friends:

What to see in Bukhara, the city of storks

“There used to be 200 pools of water in Bukhara. We called them Hauz, that is, ‘ponds’. They were the main supply of the city. People came there to chat, the elderly took shelter in the shade of the lindens to play chess and people would gather around to dance and party in the evening. The ponds were the ideal habitat for frogs and this attracted flocks of storks.

Bukhara was the city of storks. There were nests on every roof. But ponds were also a vehicle for disease. There were several epidemics and plagues. So when the Bolsheviks took the city in the 1920s, they shut down almost all the pools and modernized the water system. Without the ponds, the frogs disappeared and, as a result, the storks flew away. If you live in northern Europe, when see a stork, think of Bukhara, because maybe that stork came from here”.

Lyab-i Hauz

My hotel is in Lyab-i Hauz, a square with one of the few remaining pools in the city. Today it is filled with restaurants for tourists and stalls overlooking the pond. In the evening there is loud music, such as Al Bano and Romina’s songs or Ricchi e Poveri s. Uzbekistan seems to really love Italian old music!

Lyab-i Hauz doesn’t have the charm it used to have, and I wouldn’t have understood its historical and cultural value if Aziza, the tour guide, hadn’t explained its history to me. As we walk, I notice many stork nests coming out of the roofs.

“The nests you see are fake, to remind us of the past. There is only one real one left in the city, trying to resist the weather.”

The bazaars of Bukhara

The streets from Lyab-i Hauz to the north and west of the city lead to the three covered bazaars: the exchange market, the chapels and jewelers markets, all covered with cream-colored brick domes. They serve to channel in the fresh air and bring relief from the summer heat.

“Here you can buy everything you like,” Aziza continues, “but don’t be afraid when the trader tells you the price. They expect you to negotiate and, if you do not, they are offended“.

I go back to the market several times, in the morning and in the evening. Prices change considerably during the day, but the smile and kindness of the traders are constant!

Maghok-i-Attar mosque and the Zoroastrian temple below

In the past, there were many more covered bazaars in Bukhara – today only three survive. Where once stood the spice bazaar, now stands the Maghok-i-Attar mosque, the oldest mosque in Central Asia, dating back to the 9th century.

Legend has it that this mosque was saved from the barbarity of Genghis Khan by the intervention of the locals, who buried it to hide it. It is a truly unique place, the most sacred in the city. Below the mosque, a 5th-century Zoroastrian temple was found, later destroyed by the Arabs, and even deeper, an earlier Buddhist temple.

Zoroastrianism is the oldest monotheistic religion in the world and bears striking similarities to Christianity. Both, in fact, worship one God, creator of the universe. Both speak of free will for human beings, who are called to choose between good and evil, and both describe the day of the universal judgment, in which men will be judged for their actions.

In the heart of Bukhara: Mir-i-Arab Madrasa and Kalyan Mosque

“There are 140 protected buildings in the heart of the city, some of which are thousands of years old,” continues Aziza. “I don’t recommend trying to see them all. Instead, take the time to take a long walk. There is nothing better to breathe the atmosphere of the place”.

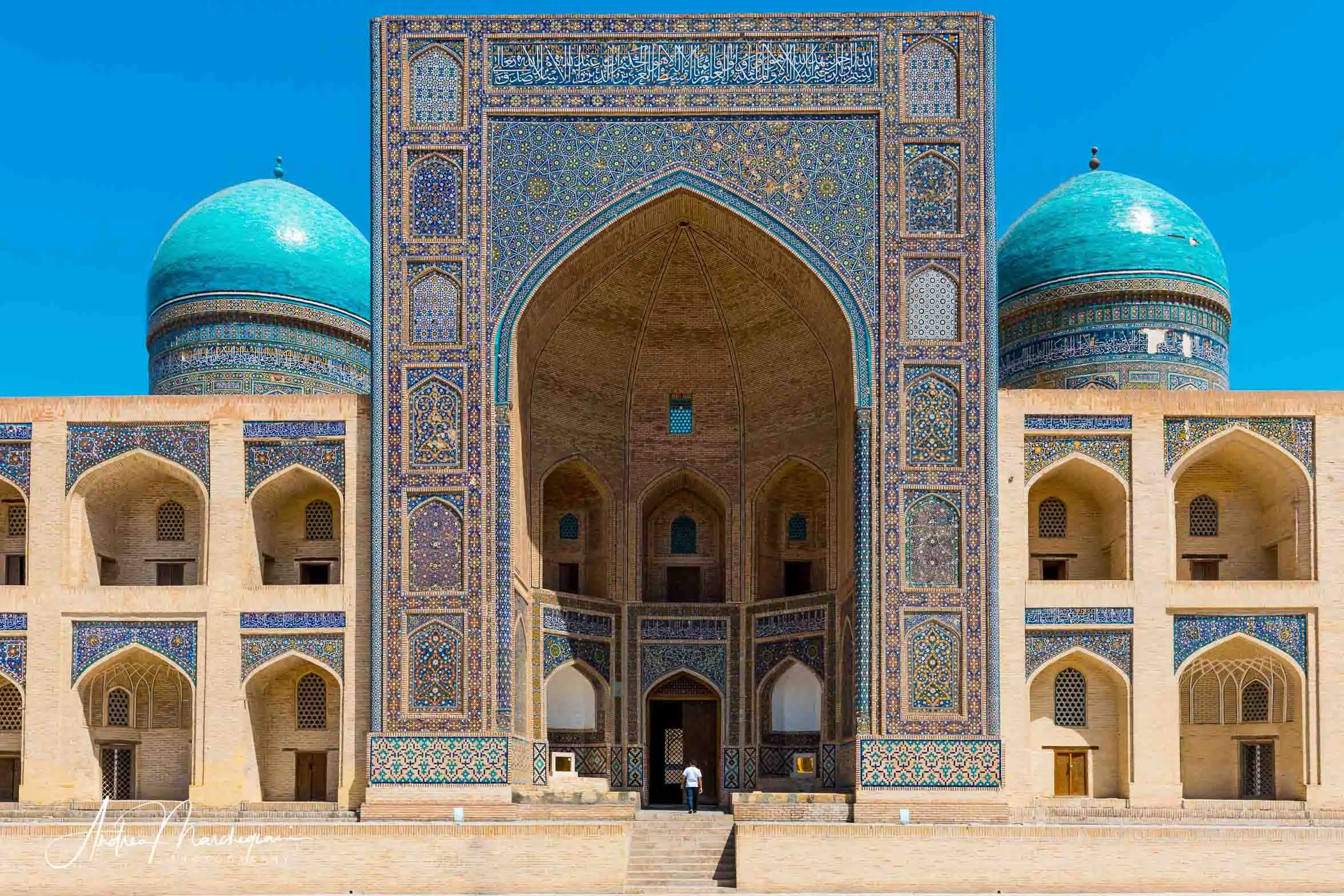

Our tour with Aziza is coming alive: the next stages will leave us breathless. I don’t know how many photographs I took at the 16th-century Mir-i-Arab madrasa, with its bright blue domes. I continued to return several times during my stay in Bukhara, until I managed to capture it in the best light (late afternoon).

The madrasa is forbidden to tourists, so you can only enjoy the amazing facade.

Opposite – and contemporary – is the equally majestic Kalyan Mosque (or Kalon). It is the city’s main mosque and can hold up to 10,000 worshippers in its inner courtyard, which features colorful tile decorations.

In the square between the madrasa and the mosque, stands a true architectural masterpiece. It is the Kalyan minaret, which dates back to 1127. 47 m high and with a 10m deep foundation, it was the tallest minaret in Asia. Genghis Khan was so impressed that he decided to spare him.

Its 14 decorated bands constitute the first example of blue enamelled tiles and inspired its use throughout the Timuride architecture. I am in the heart of Bukhara: the scenery is so exotic and picturesque it moves me to tears.

The minaret testifies to the world that beauty can soften even the heart of the most ferocious destroyer. Beauty is a longing for upliftment.

Abdoullaziz Khan madrasa and Ulugbek madrasa

As we move towards the fortress, we are attracted to one of the many abandoned madrasahs that would require a complete and rapid renovation. It is the Abdoullaziz Khan madrasah, dating from the 17th century and today a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is located in front of the dilapidated Ulugbek madrasa. The guide explains that Abdoullaziz madrasah is currently occupied by stalls and is used as a bazaar by local traders. On the other hand, the madrasah of Ulugbek, which is so run-down it does not seem to have anything special, is actually the oldest madrasah in Central Asia. It is nothing less than the madrasa used as a model for all the others, even for the Registan complex in Samarkand.

“Excuse me, why didn’t you even want to show it to us?” accuses my travel companion Daniele. Aziza is visibly embarrassed. “There’s so much to see and it’s so banged up I didn’t think you’d care,” she replies. Some of the madrasahs of Bukhara have been restored by UNESCO. I hope that more funds will soon be found, because this heritage should not be lost.

The Ark of Bukhara and Zindon

After walking for about ten minutes, we arrive in front of the Ark of Bukhara, which is the royal fortress.

It is the oldest building in the city, residence of the emirs from 400 to 1920, when it was bombed by the Russians. Even today, 80% of this structure is in ruins and it is possible to visit only some restored rooms, such as the Juma Mosque, the Prime Minister’s apartment, the court and the stables.

Do not miss the Zindon, the torture chamber, and the cockroach pit, more than 6 meters deep, where prisoners used to remain in complete darkness in the company of fleas, cockroaches and scorpions. On this site, as well as in many other Uzbek museums, you can photograph everything with your smartphone, but if you have a SLR you are forced to pay a supplement. If you are caught in the act of crime, a month in the cockroach pit will put out any desire to behave like cheeky tourists!

Bolo Hauz mosque and Chashma Ayub mausoleum

Our tour continues to the wonderful Bolo-hauz mosque, located next to one of the few remaining pools in the city. The spectacular columns carved in painted wood are considered among the most beautiful in Central Asia. Next to it, the Russians built a 33m high water tower. It could not screech more!

Nearby is the mausoleum of Chashma Ayub, the “source of Job”. Legend has it that Job planted his stick here, bringing forth a spring capable of healing from all wounds. Inside, I meet many faithful who pray and drink water with a truly evocative religious fervor.

Ismail Samani mausoleum

The tour ends with a visit to Samani Park, where Ismail Samani’s Mausoleum is located. Aziza seems to like it very much. “This mausoleum is dedicated to the founder of the Samanid dynasty. Finished in 905, it is the oldest Muslim monument in the city. It was built of terracotta bricks, with a very elaborate design that seems to change during the day, depending on the light conditions”.

Aziza tells us that, during the dry season, the terracotta works were mixed with goat’s milk because water was scarce and that this mausoleum was used as a model to build the Taj Mahal. Both stories leave me puzzled, but I appreciate the element of folklore and I decide to believe her.

“This is the only Samanid-era monument that survived the fury of Genghis Khan, because it had been buried by debris from a previous flood. It was found only in 1934 by some archaeologists. It has 2m thick walls and never needed restoration”. It must be because of the goat’s milk!

Next to the mausoleum, the Russians built a playground, complete with rides and Soviet-style panoramic wheels. Another example of stylistic integration failure!

Plov, the typical Uzbek dish

This is our last stop. I greet Aziza, who advises me to eat a good plov for dinner. It is a typical Uzbek dish, a kind of national dish, like pasta for Italians. Although each locality has its own variant, the plov has a peculiarity: it is rice stewed in zirvak, a sauce made from mutton meat, onions, chickpeas, carrots and various spices. It requires a very long low temperature cooking to get a very tender meat stew, which really melts in your mouth. I haven’t eaten anything else since I arrived in Uzbekistan and I still enjoy eating it. They also say it’s an aphrodisiac!

Shavkat Boltaev photo gallery

The next day I dedicate myself to long lazy walks and go back to the places that most impressed me. By chance, I come across the private gallery of local photographer Shavkat Boltaev.

Some elderly people are sitting in a courtyard and playing chess. I approach to photograph them and we exchange some smiles. This is how I see the entrance of the exhibition. The photographer displays and sells reportage photos of old Bukhara.

His shots are really good and range from portraits to landscapes. A photo catches my eye: you can see a mosque or a madrasa, I can’t say precisely, with four imposing towers. I ask a guy if he can tell me its name and he answers “Char Minar!“. It’s really suggestive, so I decide to find it. It will be my personal treasure hunt.

Char Minar madrasa

I walk along the alleys and ask passers-by “Char minar! Char Minar!”

They respond pointing a direction with their hand, sharing with big smiles of complicity. I like Uzbekistans, they are so open and generous!

The treasure hunt takes me to an area of the city on the edge of the old town. In a couple of junctions, I’m afraid I’ve been misled, because I’m getting lost in a maze of alleys, between municipal washhouses and dilapidated private houses. The gas pipes sprout from the pavements of the streets and are fixed to the outer walls of the houses – they arch, unwind, descend without any protection from unintentional impacts. Theere must be some divine grace keeping these pipes from blowing up!

Anyway, I keep following the signs and at the end I get to… Char Minar! Here it is!

Built in 1807 in Indian style, it is a madrasa adorned with four tiled towers. The name means “four minarets”, which reveals how confused the local people were about its actual use. In an attempt to determine whether it is a madrasa or a mosque, a family of merchants established their own souvenir shop there. When in doubt, it’s always better to be practical, right? I pay a ticket and go upstairs, being able to enjoy a close view of the towers. I long admire them: I have found my secret place in Bukhara.

A typical Uzbek hammam in Bukhara

It is late afternoon now. Tomorrow I will leave Bukhara: my trip to Uzbekistan is going to take me to Samarkand. It’s just the right time for a cuddle, so I book one of the famous Uzbek hammams.

Men and women cannot share the same spaces and there are two different structures, located in different streets, to ensure that there is no promiscuity. I imagine myself immersed under steam, sipping a hot tea and waiting to receive my massage. Reality will blow away my expectations!

A few minutes later, I find myself lying on a huge hard stone while a guy tries to scrape layers of skin off me and pulls my legs and arms as if he wanted to sprain them. “Easy, easy, please!”

Hygiene also seems to be lacking: we are all rubbed with the same rough sponges. Between one client and another, the masseur simply gives a quick squeeze to the sponge with fresh water and he is ready for the next customer.

Quite bewildered by the experience, I try to keep my disappointment to myself.

At dinner, I meet the girls of my group in front of the usual portion of plov. “Did you like the massage?” I ask my friend Giulia -yes, that Giulia. The girl with the angel face and an innate ability to attract trouble-.

“Did you guys like it?” she replies with elusive words. She looks at me with the shiny eyes of a an abandoned dog. “For us it was terrible! A big woman ordered us to strip naked, completely, then made us crawl, next to each other, in a line! She shouted “You’re dirty!” and started rubbing us hard with a rag! We seemed to have ended up in a Soviet gulag!”.

We burst out laughing. We eat our plov, sipping beer. We enjoy inventing traumas and unprecedented psychological violence, painting ourselves as survivors of the bloodiest regimes.

Indeed, travelling is not only about visiting new places, but also letting your imagination run wild every now and then and pretend you have lived an entire life somewhere else.