- Home

- Photo Galleries

- Portrait Photography

- Landscape Photography

- Street Photography

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Holy Ganges

- Varanasi

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti

- Varanasi, Manikarnika Ghat

- Varanasi Streets & Alleys

- Varanasi Demolition

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- Sarnath

- Brick Kilns

- Tamil Nadu, Chennai & Mamallapuram

- Tamil Nadu, Fort Tirumayam & Madurai

- Tamil Nadu, Tiruvannamalai & Thanjavur

- Kerala, Munnar

- Kerala, Peryiar

- Kerala, Backwaters

- Kerala, Kochi

- Kazakhstan

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Travel Blog

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Tamil Nadu & Kerala

- Varanasi

- Whato to do in Varanasi

- Varanasi Life along the Ghats

- Varanasi Death along the Ghats

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti Ceremony

- Varanasi demolished to honor Shiva

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- “Varanasi, A Journey into the Infinite”

- Sarnath

- All about River Ganges

- Holy Shit. All about Indian Cow Dung

- Clean India Project

- Brick factories

- Tilaka, pundra, bindi: what is the mark on Indian foreheads?

- Kazakhstan

- Mongolia

- Ulaanbaatar, the coldest capital in the world

- What to do in Ulaanbaatar

- Chinggis Khan Museum, 6 floors of Mongolian history

- Gorkhi-Terelj National Park and Bodgkhan Natural Reserve

- Altai Mountains, Things to do in Olgii and Sagsai

- Living with the Eagle Hunters

- Sagsai Eagle Festival

- Navrus Festival

- Xöömej, Mongolian throat singing

- Mongolian Food

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Latest Posts

- Photography Blog

- About

- Prints

Share with your friends:

Toubakouta, gateway to the Saloum River Delta

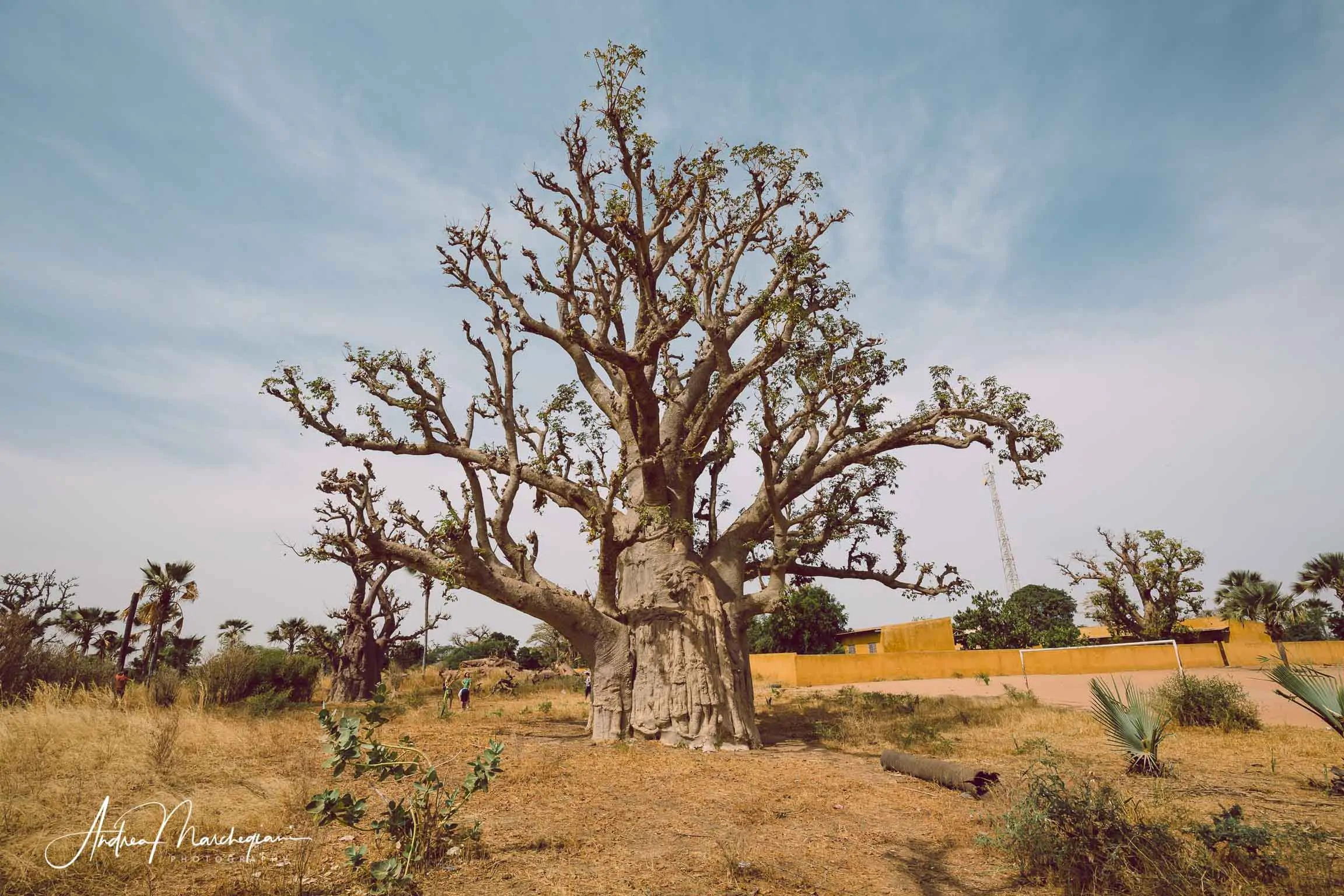

Senegal is a country that makes you think. Dakar hit me in the stomach with a visit to the island of Goree, once a strategic hub for the slave trade. The north of the country, with its arid expanses of almost desert savannah, impressed me for the presence of large solitary baobabs and the hard life of Kayar’s fishermen.

Now I leave all this behind and move south, towards Toubakouta, near the border with Gambia. The town is the best starting point for exploring the Saloum River delta, a fascinating labyrinth of over 200 islets of sand and shells.

Here, the barren vegetation of northern Senegal gives way to lush views of baobabs and mangroves, inhabited by over 250 species of birds such as pelicans, flamingos, herons, gulls and terns. The river’s fresh waters mix with the salty sea of the Atlantic Ocean, making it an ideal habitat for turtles, manatees and dolphins.

The mouth of the Saloum River, a UNESCO World Heritage Site

The Saloum Delta has been a national park since 1976 and covers over 70,000 hectares. Of these, 811 were designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 2011, due to the presence of mounds of shells, amassed by men over the centuries. These mounds have produced artificial islets, some of them hundreds of meters long, also used as burial places.

The best way to visit the area is sailing in small wooden motor boats.

Reposoir des Oiseaux

We get on a pirogue and head towards the Reposoir des oiseaux, an island of mangroves where birds nest and rest.

This part of Africa is so different from the populated places I have visited so far, all largely exploited by man. It is as if we had crossed a border: we are suddenly immersed in an ancestral, wild and powerful Africa, where uncontaminated nature reigns.

The Reposoir is full of birds. It’s funny to notice that the elegance they flaunt while flying vanishes into an embarrassing clumsiness when they land on a tree and quarrel with each other to occupy their favorite branch. “Looks like a poorly run condo,” I think to myself.

Our ferryman explains that this island is so crowded because it is enough far from the others to prevent terrestrial predators from making it a hunting ground.

The sun goes down and it’s time to go back to Toubakouta. On the way there is silence, inside and outside. At sunset, we admire the imposing black silhouettes of the baobabs standing out against the red sky. It’s landscapes like these that infect travelers with so-called ‘Africa sickness’.

The village of Diogane and the Senegalese Teranga

The next morning we get back on the boat to continue our exploration of the Saloum delta. There are many villages in this region, all isolated and dedicated to fishing.

We decide to visit the village of Diogane, which has 2,000 inhabitants, mainly because here there is a small school and an infirmary. We want to bring them medicines, pencils and notebooks.

It is an apt choice as our gesture is surely useful; moreover, it will allow us to experience Teranga, the famous Senegalese hospitality, which I must confess I found no trace of so far. In this part of Senegal, in fact, the predominant ethnicity is not the Wolof, as in Dakar and Saint Louis, but the Seher. Their kindness and welcome will always remain within me, balancing the hostility I have encountered so far.

We reach Diogane while a group of smiling children run towards the pier waving in disorderly greetings. They ask us nothing and do not cling to the search for gifts or candy. They just want to be there when we arrive and hope to be picked up and play Ring around the Rosie.

A few meters away, along the beach, fishermen are struggling with the maintenance of their boats. I’ve already seen the pirogue painting operations in Kayar, but this time instead of being chased away I’m invited to see the process. I can photograph as much as I want and chat amiably with young fishermen. One by one, they ask me to be photographed and to be able to see themselves from the camera screen. I find them all beautiful and I tell them, causing bursts of embarrassed laughter. The children don’t give up a moment and signal us to follow them.

They lead us a hundred meters from there, where people are gathering and dancing at a party. Cheerful music is playing. They explain that a wedding is taking place and ask us to take part in the festivities, as long as we undertake not to photograph the event. Africans know how to have fun in ways we have forgotten: the very presence of the guests is a source of great joy and satisfaction. And no one feels the need to seclude themselves to watch notifications on their phone!

The primary school of Diogane

The school of Diogane gives us an equally festive welcome. The children are sitting in their classes, pretty busystudying, but as soon as the teacher introduces us, they all scream out of excitement!

The children run towards us and literally drag us to their desks. They have a lot of fun seeing us sitting like normal students, turning the roles upside down. The teacher observes the scene in amusement.

I don’t think these children are used to the strict discipline of our old boarding schools. I remember myself as a primary school student, I remember the strict rules, including corporal punishment. In those classrooms you could have heard a pin drop and I am happy to see that here pins drop out of laughter. I enjoy photographing these reckless students, it is a healing experience.

“Perhaps here teachers let children free to be happy because life itself imposes its discipline”, I reflect.

Diogane is a village where fatigue is at home. The women mostly collect freshwater molluscs and oysters, which grow attached to the exposed roots of mangroves. Men fish in the river. In the village there is no electricity when there is no sun and there is no water in the tanks when it does not rain for long periods.

Dakar and the orphanage La Poupponière

Africa seems to repeat to me, like a mantra, that when you have “little” you are full of joy. But the richest countries have to ensure that this “little” does not become “too little”. Because it is a crime that cries out for revenge to know that the orphanages of Senegal are full of children who have not been abandoned by the will of their parents, but because of their poverty.

A few days after visiting Diogane, I have the opportunity to enter the orphanage of Dakar, La Poupponière. “There are very few orphans here,” explains the director. “It is mostly children whose families cannot bear the cost of raising another child. They’re leaving them here in the hope of getting them back in a couple of years.”

Walking around the rooms of the institute, I met smiles full of joy and hope, little hands stretched out to be held. Children who have nothing but an irrepressible will to live. “These two children are twins,” says the director. “We are very happy to have found a family to take them both”. I have a twin brother, too, and my heart aches at the thought of being separated from him. I look around me: all my fellow travellers have children in their arms. They smile and play, trying not to make the bitterness shine. But as soon as we leave the institute, our eyes swell from crying and we return to the hotel in silence, hatching so much, so much anger. Every place I visit in Senegal is a mirror in which I look at the reverse of myself and the society to which I belong.