- Home

- Photo Galleries

- Portrait Photography

- Landscape Photography

- Street Photography

- China

- Ethiopia

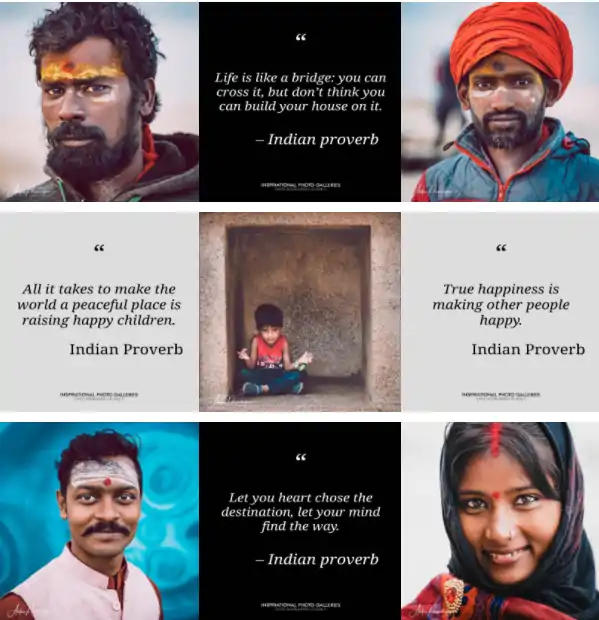

- India

- Holy Ganges

- Varanasi

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti

- Varanasi, Manikarnika Ghat

- Varanasi Streets & Alleys

- Varanasi Demolition

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- Sarnath

- Brick Kilns

- Tamil Nadu, Chennai & Mamallapuram

- Tamil Nadu, Fort Tirumayam & Madurai

- Tamil Nadu, Tiruvannamalai & Thanjavur

- Kerala, Munnar

- Kerala, Peryiar

- Kerala, Backwaters

- Kerala, Kochi

- Kazakhstan

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Travel Blog

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Tamil Nadu & Kerala

- Varanasi

- Whato to do in Varanasi

- Varanasi Life along the Ghats

- Varanasi Death along the Ghats

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti Ceremony

- Varanasi demolished to honor Shiva

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- “Varanasi, A Journey into the Infinite”

- Sarnath

- All about River Ganges

- Holy Shit. All about Indian Cow Dung

- Clean India Project

- Brick factories

- Tilaka, pundra, bindi: what is the mark on Indian foreheads?

- Kazakhstan

- Mongolia

- Ulaanbaatar, the coldest capital in the world

- What to do in Ulaanbaatar

- Chinggis Khan Museum, 6 floors of Mongolian history

- Gorkhi-Terelj National Park and Bodgkhan Natural Reserve

- Altai Mountains, Things to do in Olgii and Sagsai

- Living with the Eagle Hunters

- Sagsai Eagle Festival

- Navrus Festival

- Xöömej, Mongolian throat singing

- Mongolian Food

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Latest Posts

- Photography Blog

- About

- Prints

Share with your friends:

Fulani, Peul or Mbororo, a people of nomadic shepherds

The first ones who come to greet me are the children. They jump around me looking for a gift. We made some dog balloons for them to play. They are smiley, joyful, vital -they are the future of this group of Peul (or Fulani), who lives near Sagatta, in Senegal.

The Fulani nomads are a people dedicated to pastoralism that wanders from Mauritania to Cameroon in search of grasslands free from cultivation. Their origins are ancient: they are supposed to come from the high Nile, which gives their features a sophisticated beauty.

Peuls have arrived in Senegal migrating. Here they converted to Islam and some tribes became sedentary, with great contempt for others who still follow the original nomadic traditions.

They prefer their cattle to have big horns and they are so tied to their animals they actually name their children after the most beautiful bulls and cows. Their society is based on the principles of freedom, dignity and beauty.

Fulani - Livestock and beauty as absolute values

I enter the village in the middle of the afternoon. The straw huts, of circular design, are intended for a single family.

The women approach intrigued. Their lips are painted black and they wear many jewels. They let themselves be photographed, but only after having checked, with the help of a friend, they are well groomed. They pose without shame or shyness. It seems that the Islamic religion has not affected their original values.

The Peul, also called Fulani or Mbororo (lit. “those who do not wash and live in the steppe”), have a society without hierarchies and are proud of two things: their livestock and their physical beauty.

They are as jealous of their cows as they are proud to show off their attractiveness. Slender, with lean bodies, big eyes and wide foreheads, they have very white teeth and small noses. Their skin is not as black as the Senegalese, but comparable to the Middle Eastern populations.

They have an elegant attitude, both women and men, and believe that their beauty is a gift from God.

Peul women choose the most beautiful man

Physical appearance is so important to them that a husband willingly gives his wife to another man as long as he is handsome, hoping to have a more beautiful son.

Women also enjoy the right to choose their partner.

Every year the nomads organize a big party, called Yake, during which the men dress up and dance for the young unmarried girls, competing to be chosen.

The cattle market in Sagatta

I reach Sagatta cattle market, not far from the village. The atmosphere here is different. Jealousy for cattle takes over the shepherds, all men, and I am pointed out, scolded and dismissed. Once again, I face Senegal’s distrust of foreigners.

Everyone should come to Senegal, I repeat to myself. Everyone should understand what it means to be judged at first glance for your cultural diversity, for your skin color.

I came to their house to spy on the features of their beautiful cows, they must be thinking. I have the arrogance to steal this beauty and bring it home in the form of a picture. But it is them who have adapted their lives to the needs of livestock, they are the ones who live the bare minimum, always ready to move elsewhere when the grass becomes sparse and the dry season arrives. That’s what makes their cattle so healthy and beautiful. I should not try to take this beauty in any way, shape or form. It is rightfully theirs.

I turn away from the Bororos, struck by their charm. Yet I can’t feel them close. They have made it clear, once again, that I am a foreigner here. I can try to approach them, but I will never be one of them. My wealth is made of material goods, like the reflex camera I photograph them with. But they are the real winners, they have received beauty as a gift from God.