- Home

- Photo Galleries

- Portrait Photography

- Landscape Photography

- Street Photography

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Holy Ganges

- Varanasi

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti

- Varanasi, Manikarnika Ghat

- Varanasi Streets & Alleys

- Varanasi Demolition

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- Sarnath

- Brick Kilns

- Tamil Nadu, Chennai & Mamallapuram

- Tamil Nadu, Fort Tirumayam & Madurai

- Tamil Nadu, Tiruvannamalai & Thanjavur

- Kerala, Munnar

- Kerala, Peryiar

- Kerala, Backwaters

- Kerala, Kochi

- Kazakhstan

- Myanmar

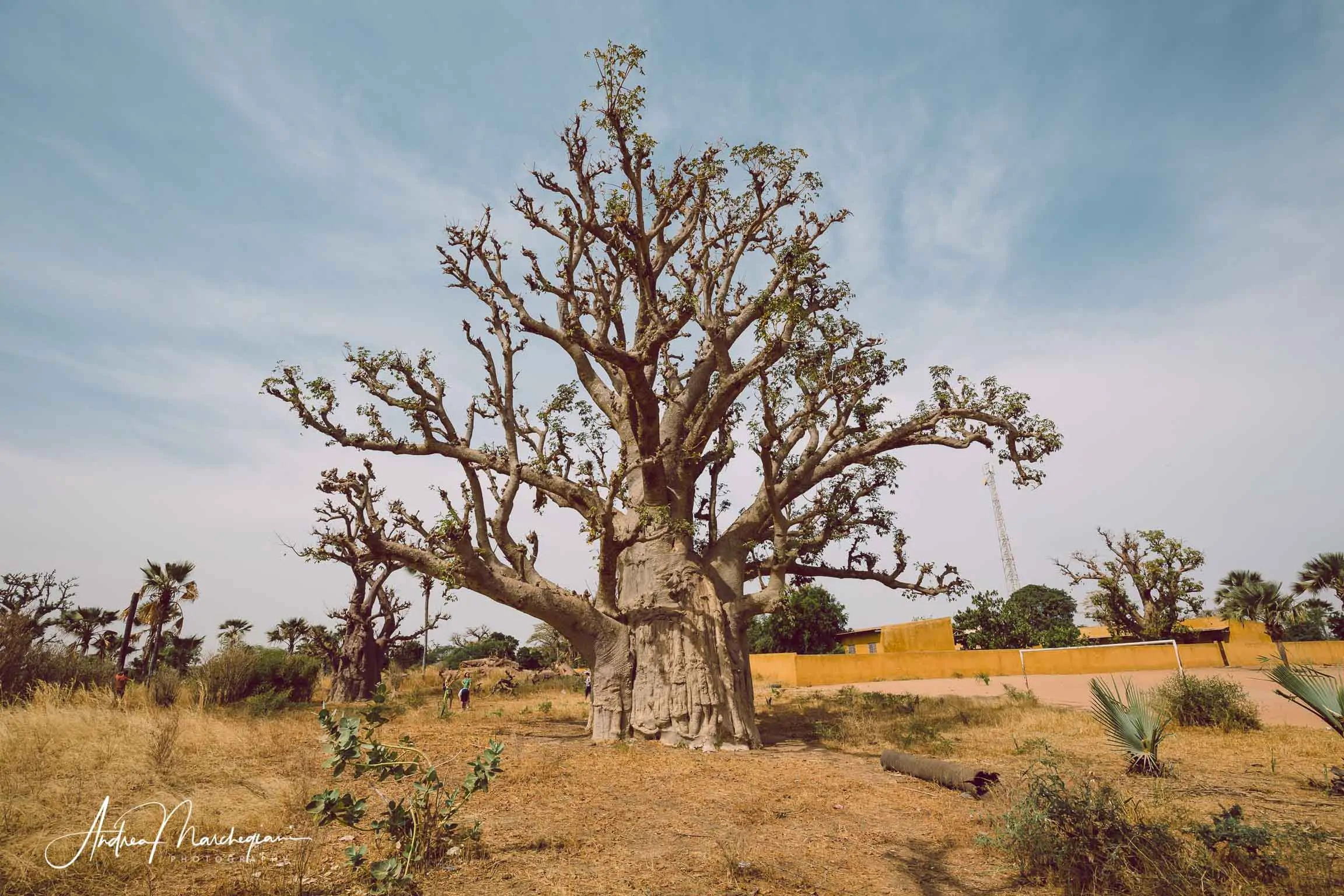

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Travel Blog

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Tamil Nadu & Kerala

- Varanasi

- Whato to do in Varanasi

- Varanasi Life along the Ghats

- Varanasi Death along the Ghats

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti Ceremony

- Varanasi demolished to honor Shiva

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- “Varanasi, A Journey into the Infinite”

- Sarnath

- All about River Ganges

- Holy Shit. All about Indian Cow Dung

- Clean India Project

- Brick factories

- Tilaka, pundra, bindi: what is the mark on Indian foreheads?

- Kazakhstan

- Mongolia

- Ulaanbaatar, the coldest capital in the world

- What to do in Ulaanbaatar

- Chinggis Khan Museum, 6 floors of Mongolian history

- Gorkhi-Terelj National Park and Bodgkhan Natural Reserve

- Altai Mountains, Things to do in Olgii and Sagsai

- Living with the Eagle Hunters

- Sagsai Eagle Festival

- Navrus Festival

- Xöömej, Mongolian throat singing

- Mongolian Food

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Latest Posts

- Photography Blog

- About

- Prints

Share with your friends:

Kayar, the largest artisanal fishing center in Senegal

Still impressed by the visit to Goree island, we get up early to reach Kayar fishing harbour. What I’m about to see will fill my eyes with wonder.

Kayar is a village about 60 km north of Dakar and is home to one of the largest fishing centers in Senegal. You would expect large boats equipped with industrial fishing systems and instead we are faced with an endless parade of pirogues, small traditional boats made of colored wood. Each boat has its own decorated motif, which identifies the family it belongs to. They colorfully dot the horizon as they wait for their turn ashore, when they will start unloading their precious loot.

The beach is teeming with busy people. There’s a lot going on. Each team goes between their boat and the beach, loading the catch in large plastic crates which they carry on their heads.

The operation is artisanal and the fish overflowing from the basket falls on the sand, swaying at every step. Children run for it, put it in their shirts and run away. Even today they have a meal for their family.

The fish is thrown from the crates directly to the ground, where the women have laid large plastic sheeting. They are responsible for selling the fish on site, although most are then moved in large refrigerators piled a few meters back. They’re not plugged into any power outlets, and, from their poor looks, I doubt they’d work anyway.

Precautions needed in taking photographs in Senegal

My gaze is drawn to a fisherman returning from the boat, with his big and heavy basket on his head. He points with his hand at a point and shouts something, his expression is full of disgust. I look for the cause of so much reprobation and I find Tiziana, a traveling companion, who is taking a picture with her mobile phone. Around her, some fishermen tell her to put away her smartphone. In a few minutes we all receive the same warning. It is forbidden to take photographs.

I am surprised by the hatred with which we are told to get out of the way, to move away from the fishermen’s route, to hide the cameras.

Basically, each of our steps is monitored by some local that alerts others if we try to photograph something. We have to argue just to bring home a detail of the fish scattered on the beach.

“It’s an extraordinary activity”, Barbara tries to say to our guide. “We photograph because all this fascinates us”. But the situation does not improve. The lack of hospitality that we are experiencing unfortunately will accompany us throughout our stay.

However, I decide to take some shots, mounting my telephoto lens and trying to be discreet. I am witnessing an exceptional activity, hardly balanced between past and future, and my soul as a reporter does not accept any prohibition. As I photograph, I understand that only some people scold us; others, instead, smile and accept our presence.

I get lost on this immense beach, confusing myself with the locals; I observe closely their work and I fully enjoy every moment. The whole village is engaged in this activity and the sense of community is something we Westerners are no longer used to.

Senegal, the crisis in small-scale fishing

The Senegalese Sea is among the most fishy in the world. It provides work for about one and a half million people. The fish sector is not only about fishermen, but also the whole transport and resale sector, which involves neighbouring countries.

However, the amount of fish in the area has fallen by 80% over the past decade and it is estimated that in the next 10 years, local fish stocks could disappear altogether.

The reason for this is the reckless activity of the Chinese, European and Russian multinationals which have flooded Senegalese waters with hundreds of fishing vessels. Each of these can catch up to 20,000 tons of fish per year, the equivalent of the annual catch of about 1,700 Senegalese pirogues. Most of the catch is used to feed livestock on intensive farms, which means that about 25% of Senegalese fish are not directly used for human consumption.

Every year, about 1.9 billion fish are missing from African markets, with a sharp impoverishment of the local population. A few years ago, Mame Fatou Kaire, a Senegalese fishing entrepreneur, denounced the situation by warning that the activities of foreign fishing vessels are producing large-scale unemployment. More and more people will decide to fight for a better future, migrating to Europe. And Europe will be divided between those who would like to host them all and those who want immigrants to stay where they are and try to “help them in their home country”.

If you are wondering why Senegal is not taking political decisions on this, it is good to know that they have already tried. To protect local fishermen, the Senegalese Government has in recent years stopped licensing foreign vessels.

However, a number of vessels continue to operate from neighbouring countries such as Mauritania, not to mention the fact that fishing licences continue to be obtained in Senegal as a result of the corruption of local politicians. The world is a system of communicating vessels. What comes around goes around and we should stop acting surprised.