- Home

- Photo Galleries

- Portrait Photography

- Landscape Photography

- Street Photography

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Holy Ganges

- Varanasi

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti

- Varanasi, Manikarnika Ghat

- Varanasi Streets & Alleys

- Varanasi Demolition

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- Sarnath

- Brick Kilns

- Tamil Nadu, Chennai & Mamallapuram

- Tamil Nadu, Fort Tirumayam & Madurai

- Tamil Nadu, Tiruvannamalai & Thanjavur

- Kerala, Munnar

- Kerala, Peryiar

- Kerala, Backwaters

- Kerala, Kochi

- Kazakhstan

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Travel Blog

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Tamil Nadu & Kerala

- Varanasi

- Whato to do in Varanasi

- Varanasi Life along the Ghats

- Varanasi Death along the Ghats

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti Ceremony

- Varanasi demolished to honor Shiva

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- “Varanasi, A Journey into the Infinite”

- Sarnath

- All about River Ganges

- Holy Shit. All about Indian Cow Dung

- Clean India Project

- Brick factories

- Tilaka, pundra, bindi: what is the mark on Indian foreheads?

- Kazakhstan

- Mongolia

- Ulaanbaatar, the coldest capital in the world

- What to do in Ulaanbaatar

- Chinggis Khan Museum, 6 floors of Mongolian history

- Gorkhi-Terelj National Park and Bodgkhan Natural Reserve

- Altai Mountains, Things to do in Olgii and Sagsai

- Living with the Eagle Hunters

- Sagsai Eagle Festival

- Navrus Festival

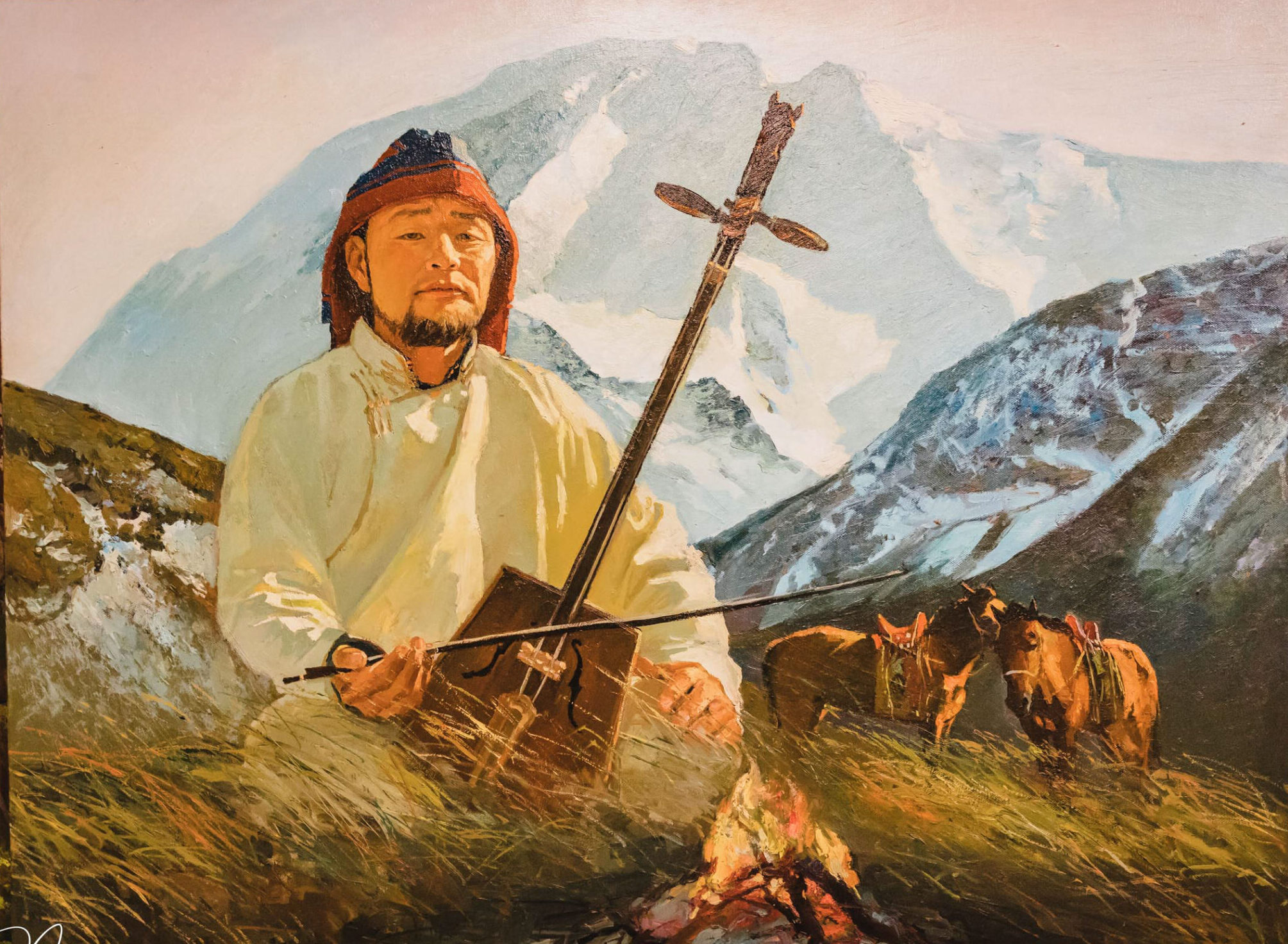

- Xöömej, Mongolian throat singing

- Mongolian Food

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Latest Posts

- Photography Blog

- About

- Prints

The Chinggis Khan Museum is the most beautiful museum in Ulaanbaatar. Modern, elegant and well thought out, it offers visitors the best possible experience and a historical tour of the country from prehistory to the present day. If you are on a tight schedule and can only see one museum during your trip to Mongolia, make sure this is it.

Share with your friends:

Opened in 2022, the Chinggis Khan Museum collects more than 12,000 artifacts first crammed into state archives or on display in Russia and the United States. It is the most comprehensive review of Genghis Khan’s empire and later. The building is spread over 6 floors, connected by escalators and elevators, and requires a visit of no less than 3 hours. Believe me, it’s worth it all!

Due to the recent opening, there is still little news about the Chinggis Khan Museum. His existence is not even mentioned on those tour guides still waiting to be updated. This is why I decided to deal with the subject in detail, especially to convince the doubters to devote the necessary time to it.

Below, I collect the information I managed to write down during my visit: nothing exhaustive or organic, notes I hope you will find interesting.

The building

The building that houses this beautiful museum was once dedicated to the National Museum, then became the National History Museum. Damaged by use and time, it was completely renovated 8 years ago and finally destined to celebrate the memory of the greatest Mongolian hero.

Unlike other Mongolian museums, here you can not take pictures inside, not even paying a surcharge. The only photos online are, not surprisingly, those of the amazing external facade, with the golden portal, and the internal staircase that connects the first floor to the ground floor, where there is the ticket office, the wardrobe and a bar.

I recommend leaving backpacks and cameras in guarded lockers: do not carry them during the visit, you will get tired unnecessarily.

It is, from my point of view, essential to have with you a guide who speaks good English: he can help you connect the various Mongolian historical eras and direct your attention to the most significant finds.

I was lucky enough to be led by Sanjaa, a man of extraordinary culture provided by Wonder Tours & expeditions of Mongolia, a tour operator I can only praise by my personal experience.

The history of Mongolia divided into six floors

The six floors of the museum take 3 to 5 hours to visit, but they are really worth it. The historical excursus starts from prehistory to the present day: the finds are placed in chronological order offering a journey into the most important events of the Mongolian people.

First Floor

The first floor shows finds dating from the Iron Age (3,000 years ago), mostly stems and tombs with slabs, and retraces Mongolian history up to the 5th century AD.

An interesting section is reserved for the first Mongol emperor Hon (third century BC): funeral practices, techniques of making jewelry, horse decorations, leather and silk fabrics.

Decorations show recurring drawings of deer and wolves, symbolizing respectively the mother and father. The Sun and moon represent the cycle of life.

Findings of the Second Mongol Empire, headed by the tribes of Chuchan, are next.

Second Floor

On the second floor you can see the remains of the Turkish Empire (552-745 AD), including jewels, musical instruments, bows and arrows, again horse decorations (apparently the Mongols loved to bejewel their trusty steeds!).

Many statues of the time have their heads cut off, because the Uyghurs (or Uyghurs), who succeeded the Turks and reigned between 744-840, beheaded the statues to erase their memory. Interesting finds from the tomb of Shoroon Bumbagar come next.

After that, the remnants of the Khitai dynasty, who ruled between the 10th and 12th centuries, are displayed.

Third Floor

The Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan, who reigned from 1206 to 1260, appears on the third floor. In fact, the Mongols call it Chinggis Khan, we have always transcribed and pronounced it the wrong way.

The presence of a guide becomes from this moment essential not to be immersed in a large amount of objects and finds whose specific characteristics would be difficult to distinguish.

From the way Sanjaa speaks, I understand Mongolians identify culturally and ethnically mainly with the tribes of Genghis Khan, which originate from the Ulaanbaatar area (much less with the others, especially Manchurians, who they consider Chinese).

The weapons Genghis Khan’s army used are shown in this section, proving how innovative he was. He manage to build the second-largest empire in history, extending from Khwarezmia to Korea, on a surface of 24 million km², with a population of over 100 million people.

War Strategies by Genghis Khan

Sanjaa explains to me Genghis Khan had a precise war strategy:

1. Propaganda: Genghis Khan sent infiltrators to the places he wanted to attack, with the sole purpose of frightening the population. His messengers described Mongols as a people of ruthless, inhuman savagery, whose army it was better not to deal with. This technique of psychological manipulation brought most cities to surrender without fighting. This way, Genghis Khan guaranteed safety. Cities that decided to fight were razed to the ground. Only a small percentage of survivors were allowed to survive, so they could run the to the close villages and spread the word, becoming unwitting tools of the Mongol propaganda machine.

2. Biological warfare: Mongols threw rotting corpses over the walls of besieged towns. This facilitated the spread of disease and decimated the besieged population. In the museum you can admire the innovative catapults designed by the Mongols.

3. War technology: Genghis Khan invented new war tools. The swords, for example, were not designed to cut ( the Mongol soldiers fought on horseback) but as blunt objects. They were meant to break collarbones and thus prevent the opponents to use their arms to fight back; horses were so important the fighters had spare ones just in case. But the main innovation was the creation of small, light and space-saving arches, usable without having to get off the horse. Made of bones covered with strips of horse skin, they were however suitable only for dry Mongolian climates, while they could not stretch properly in case of excessive humidity.

Fourth Floor

The fourth floor collects finds ranging from the 13th to the 15th century.

A section is dedicated to Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis. This is the time where Marco Polo lived. The empire’s capital had been moved to Beijing. Some believe this choice proves Kublai Khan’s cosmopolitan mentality, others think it was a betrayal of Mongol values. Truth is the old capital was isolated, in the middle of the steppes, and little connected to the rest of the imperial lands. Beijing was definitely more central and a better choice. The finds show the sophistication of the costumes of the time and the model with the reconstruction of the summer palace is remarkable.

Under Kublai Khan, Mongolia attempted to invade Japan twice, but with little success. Not being a people of sailors, the Mongols embarked on low-performance cargo ships and were repulsed harshly. They tried again, after equipping themselves with warships, but a massive earthquake followed by a tsunami decimated the army.

Subsequently, the empire began to disintegrate and ended irretrievably under Chinese control. As the finds show, the Mongol khans succeeded quickly, often killing each other.

Fifth Floor

The fifth floor contains objects ranging from the 15th to the 20th century and dating back to the Manchu domination.

In 1600s, the Chinese introduced Buddhism to Mongolia in order to tame its belligerent spirit. The conversion was an extraordinary success and the Mongol territory changed its face, turning into a flower garden of monasteries.

In 1700s, when Manchuria conquered China, they also took control of Inner and Outer Mongolia. The Dzungar Khanate western Mongol tribes resisted for a long time, resulting in a bloody war that lasted 70 years. Exhausted by the continuous reprisals, the Manchus solved the problem at its root, implementing a programmatic genocide that produced about 800,000 victims, 80% of the entire population.

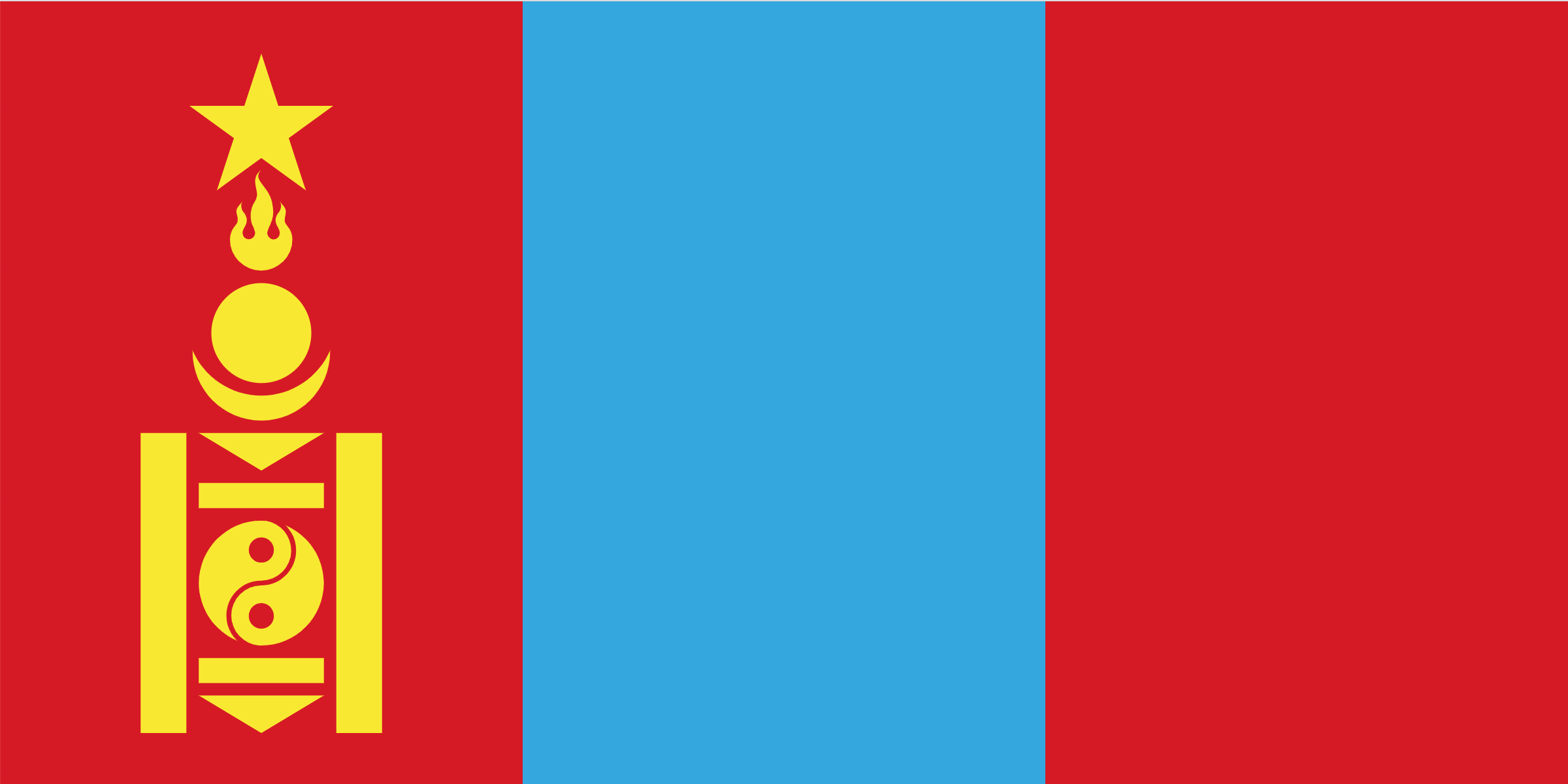

Mongolia under the Manchus maintained autonomous legislation, however, led by a Manchu-chosen leader among Tibetan monks. Zanabar, the first Jebtsundamba Khutuktu of the country, was a priest-ruler who held both spiritual and temporal power. Considered a sort of Mongolian Michelangelo, he was a great artist and intellectual. Zanabar was also the creator of the Sojombo symbol (or Soyomb), which is depicted on the Mongolian flag.

Sanjaa explains its meaning, leaving me speechless.

Meaning of the Mongolian Flag

On top is a flame with 3 points, symbolizing present past and future. Just below are the sun and the moon, symbols of the alternation of life and death; going down, there is the symbol of yin and yan, which represents man and woman, who are equal (this is what the two horizontal bars placed above and below mean). The Mongolian people are founded on this equality. On the sides, two vertical elements represent the need to defend against enemies, while the 2 arrowheads indicate the ability of the Mongols to protect the homeland.

During the Soviet period, the Sojombo was topped by a star, symbol of communism, now removed.

Sixth Floor

The sixth floor is dedicated to “Mongolia and the rest of the world”.

Here are collected documents and finds no longer shown chronologically, but thematically. It is a celebration of the technical and cultural advances Mongolia has brought to the world: the innovative war tactics, the enviable level of social security achieved during the so-called pax mongolica and religious contributions of Mongolia to Buddhism.

At the end of your visit to the Chinggis Khan Museum, with exhibits, models and audio-visual, you will feel like you have experienced the entire Mongolian historical arc. Time flies by walking between floors, even for those who usually get bored visiting museums.