- Home

- Photo Galleries

- Portrait Photography

- Landscape Photography

- Street Photography

- China

- Ethiopia

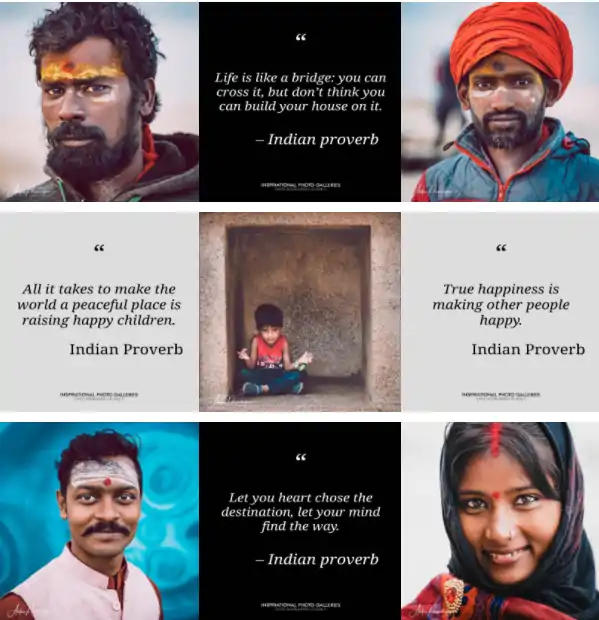

- India

- Holy Ganges

- Varanasi

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti

- Varanasi, Manikarnika Ghat

- Varanasi Streets & Alleys

- Varanasi Demolition

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- Sarnath

- Brick Kilns

- Tamil Nadu, Chennai & Mamallapuram

- Tamil Nadu, Fort Tirumayam & Madurai

- Tamil Nadu, Tiruvannamalai & Thanjavur

- Kerala, Munnar

- Kerala, Peryiar

- Kerala, Backwaters

- Kerala, Kochi

- Kazakhstan

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Travel Blog

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Tamil Nadu & Kerala

- Varanasi

- Whato to do in Varanasi

- Varanasi Life along the Ghats

- Varanasi Death along the Ghats

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti Ceremony

- Varanasi demolished to honor Shiva

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- “Varanasi, A Journey into the Infinite”

- Sarnath

- All about River Ganges

- Holy Shit. All about Indian Cow Dung

- Clean India Project

- Brick factories

- Tilaka, pundra, bindi: what is the mark on Indian foreheads?

- Kazakhstan

- Mongolia

- Ulaanbaatar, the coldest capital in the world

- What to do in Ulaanbaatar

- Chinggis Khan Museum, 6 floors of Mongolian history

- Gorkhi-Terelj National Park and Bodgkhan Natural Reserve

- Altai Mountains, Things to do in Olgii and Sagsai

- Living with the Eagle Hunters

- Sagsai Eagle Festival

- Navrus Festival

- Xöömej, Mongolian throat singing

- Mongolian Food

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Latest Posts

- Photography Blog

- About

- Prints

Share with your friends:

To Have or To Be?

All the religions of the world indicate the way of being as the only way to go to live in peace with ourselves and with others. Nevertheless, men continue to cling to materiality, in the desire to possess more and more. The smartest ones reach top social positions.

John Lennon called the leaders of the world “psychopathic madmen”, but isn’t it undeniable they are “successful men”? After all, with the extraordinary goals they reach, don’t they prove to be the ones who know what the world is about?

Yet, there is still the possibility of a society based on spirituality. There are places where a simple and essential life is sought after and appreciated, where you have only the bare necessities and dedicate your time to pray, meditate and reflect on the meaning of things. Labrang, in China, is one of these places.

Labrang, one of the 6 largest Buddhist monasteries in the world

Located 3000m high, in a valley between the mountains of the Tibetan plateau, Labrang is one of the 6 largest monasteries of Buddhism. Founded in 1709, it belongs to the religious school of the Gelugpa, also known as “Yellow Hats School”, whose supreme head is the Dalai Lama. It occupies almost 900 hectares of land and includes 10,000 rooms, painted white, red and yellow depending on their function. It is home to a university, which has a large library, many important rituals and ceremonies take place here. The monastery also houses the highest number of monks living outside Tibet. There used to be 4,000 monks but today the Chinese government has limited its number to about 1,500.

I arrive in the late afternoon. I walk along the long paths that cross the university city from one side to the other. I still have the magic of Langmusi in my eyes, the intimacy of its dirt alleys and the timeless lifestyle of the local monks and villagers. Here the atmosphere is very different, definitely more worldly. The houses are newly painted and renovated. The pavements are being rebuilt and, turning every corner, you come across construction sites of new buildings. In the street, students-monks enliven the atmosphere with the purple of their cassocks. But there is nothing spiritual in them: they talk or write messages on the cell phone. Some get into taxis, others drive state-of-the-art SUVs. Labrang is a city that is changing face.

“I imagined Labrang as a lost paradise while it’s all a construction site. Vodafone China already offers maximum coverage”, I mutter. “This place hosts a large number of faithful,” replies my friend Daniele. “What’s wrong with using offerings to improve the quality of life of monks? Basically we live in a technological age: it is not necessary to suffer inconvenience unnecessarily”. To have or to be? Perhaps spiritual awakening lies in between.

Labrang's hard past

“Here we study the history of Buddhism,” says the guide during a tour of the main temples. “I will not try to make a synthesis: Buddhism has multiple traditions with endless intersections. Studying them is more complicated than the iOS system of iPhone“. The young monk, smiley and chubby, takes a short break to wait for the visitors’ laughter to subside. “But all these traditions are based on one rule: compassion. We have no other.

Muslims have many rules. For example, they are forbidden to drink alcohol, yet at night they get drunk and drive their cars and crash against the street light poles. What good is their rule then?“

The dig at Islam is so direct and politically incorrect it is mindblowing. Yet, Labrang has a particular story. Between 1917 and 1930, the Hui armies (an ethnic group of Chinese Muslims) tried several times to occupy the monastery, setting it on fire. After each defeat, the monks rose again and drove the occupier back. The Hui responded with a new military expedition, sowing new horror. In the most bloody reprisals, the monks were burned and beheaded. Their heads were hung on wooden poles, scattered throughout the city, while the Hui military camp was adorned with the heads of Tibetan children as garlands. What is the use of a religious faith full of rules, when you feel free to contravene them all?

With all these feelings in my heart, as I try to overcome the historical dualism of being and having, of spirituality and worldliness, I walk the outer perimeter of the monastery. Dozens of faithful accompany me. It is a long journey. Besides, Labrang has the longest row of prayer wheels in the world.