- Home

- Photo Galleries

- Portrait Photography

- Landscape Photography

- Street Photography

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Holy Ganges

- Varanasi

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti

- Varanasi, Manikarnika Ghat

- Varanasi Streets & Alleys

- Varanasi Demolition

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- Sarnath

- Brick Kilns

- Tamil Nadu, Chennai & Mamallapuram

- Tamil Nadu, Fort Tirumayam & Madurai

- Tamil Nadu, Tiruvannamalai & Thanjavur

- Kerala, Munnar

- Kerala, Peryiar

- Kerala, Backwaters

- Kerala, Kochi

- Kazakhstan

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Travel Blog

- China

- Ethiopia

- India

- Tamil Nadu & Kerala

- Varanasi

- Whato to do in Varanasi

- Varanasi Life along the Ghats

- Varanasi Death along the Ghats

- Varanasi Ganga Aarti Ceremony

- Varanasi demolished to honor Shiva

- Varanasi Fruit Market

- “Varanasi, A Journey into the Infinite”

- Sarnath

- All about River Ganges

- Holy Shit. All about Indian Cow Dung

- Clean India Project

- Brick factories

- Tilaka, pundra, bindi: what is the mark on Indian foreheads?

- Kazakhstan

- Mongolia

- Ulaanbaatar, the coldest capital in the world

- What to do in Ulaanbaatar

- Chinggis Khan Museum, 6 floors of Mongolian history

- Gorkhi-Terelj National Park and Bodgkhan Natural Reserve

- Altai Mountains, Things to do in Olgii and Sagsai

- Living with the Eagle Hunters

- Sagsai Eagle Festival

- Navrus Festival

- Xöömej, Mongolian throat singing

- Mongolian Food

- Myanmar

- Senegal

- Uzbekistan

- Latest Posts

- Photography Blog

- About

- Prints

Travel photographer and blogger, Andrea Marchegiani, takes us on a journey to discover the natural beauty of Senegal, one of the most hospitable countries in Africa.

© Article and Photos by Andrea Marchegiani. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited.

Permission granted for publication in PHOTO PROFESSIONAL, August 2019.

Share with your friends:

BIO | Andrea Marchegiani is a travel photographer and blogger. He graduated from DAMS in cinema and screenwriting with a thesis on road movies. He furthered his studies by attending courses in journalism, photography, video shooting, and editing. A deep interest in foreign peoples and cultures has driven him to visit destinations that are less frequented by mass tourism, such as Ecuador, Kazakhstan, Myanmar, China, Nepal, Ethiopia, Botswana, and more. In his travel blog, he combines his passion for photography with his love for writing.

Can you tell us about your experience in Senegal? What struck you the most about this country?

I embarked on my journey to Senegal during the Christmas holidays, enticed by the idea of spending an unusual New Year’s Eve in the colonial city of Saint Louis and exploring the Djouji National Park with its rich birdlife, as well as the Lompoul Desert with its deep starry skies. However, it was other destinations that left a lasting impression, perhaps less leisure-oriented but allowing me to connect more closely with the history and everyday reality. Such places include the island of Goree and Joal Fadiouth.

Goree is located just a few kilometers from the port of Dakar, in the westernmost part of Africa. Today, tourists stroll through charming colorful streets lined with fascinating colonial-style buildings, creating a carefree atmosphere. However, for centuries, Goree held a tragic significance as a hub for the slave trade. Millions of African men and women were forcibly taken from their lands and deported to the United States to work in cotton and sugarcane fields. A guided tour of the House of Slaves is a necessary stop to better understand this tragic chapter in history and ensure that it is not repeated.

Joal Fadiouth, on the other hand, stands out for the message of religious tolerance it conveys. Joal is a small fishing village located on the Petite Côte in the south of the country. A wooden bridge connects it to the islet of Fadiouth, entirely formed by empty seashells accumulated over the centuries by shellfish gatherers. Stretching only a few hundred meters, the island serves as a cemetery.

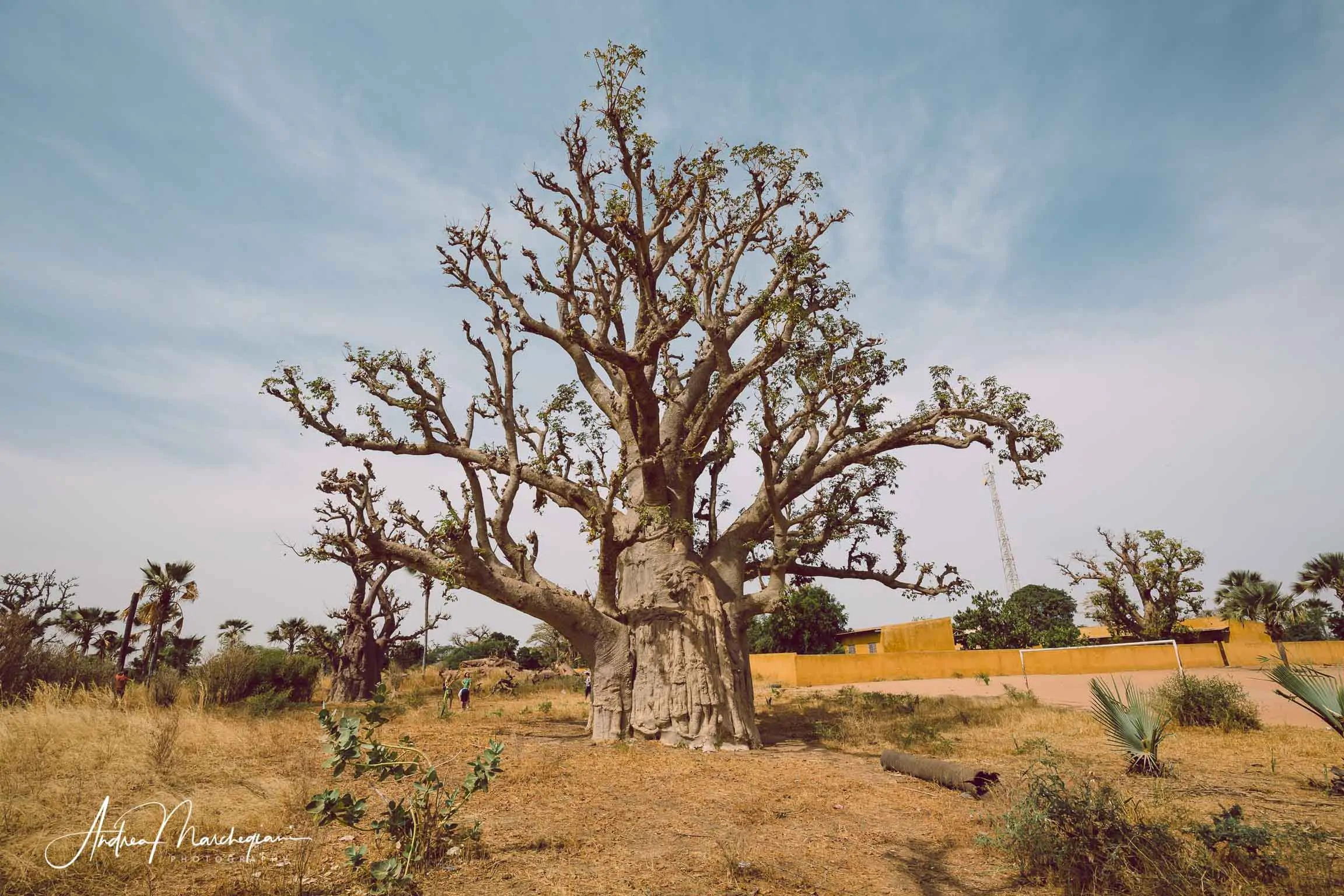

There is profound wisdom in the ecology of this process: the fishermen rest among the very shells they once caught in their lives. Fadiouth is also the only cemetery in Senegal where Christians, Muslims, and animists are buried together. While strolling along the shaded paths, adorned with imposing baobab trees, each family honors the memory of their deceased loved ones. The fishermen of Joal Fadiouth seem to tell us that no religious creed can separate the destinies of those who have fished in the same sea.

Among your images, there are beautiful portraits. Are people in Senegal willing to be photographed? In general, what is the right approach to have with the local population?

One must be very respectful and understand if there is a willingness to be photographed. This advice, valid in general, becomes a crucial issue in Senegal. People here are not accustomed to international tourism and are very wary. In Kayar, one of the largest artisanal fishing ports in Senegal, the reception was very cold. The fishermen still use small, colorful wooden boats, each with a unique decoration that identifies the owner. When the pirogues return to the mainland, it is a breathtaking spectacle.

The fishermen shuttle frantically between the beach and the boats, carrying large crates overflowing with fish on their heads. The women clean and pack the fish into separate containers, while the poorest children collect the fish that has fallen from the crates and run off to bring it to their families.

I would have spent hours photographing this scene, but the fishermen made it clear that they did not appreciate being photographed, so I left after a few minutes.

I encountered the same hostility elsewhere. It was an oyster harvester in Joal Fadiouth who explained the reason to me. For Senegalese people, it is embarrassing to be photographed while dirty and in work clothes. Therefore, it is essential to always understand the circumstances. I also found a lot of hospitality.

The Fulani, for example, who consider themselves the most beautiful ethnic group in the world, willingly pose for photographs, and the women adorn themselves as soon as they see a camera.

What advice would you give, from an organizational point of view, to those who want to visit Senegal? Is it good to rely on a guide?

You can organize your trip through an agency from Italy or manage it on your own by contacting local guides who often speak excellent Italian. They will be able to direct travelers and help them avoid unpleasant experiences.

What is the best season to visit Senegal from a photographic perspective, and what are the must-see places?

The best time to visit Senegal from a photographic perspective is from November to February when there is no rainfall, clear skies, and… no mosquitoes! The temperatures are also pleasant, warm but not scorching. Senegalese people complain about the cold whenever the temperature drops below 30°C, but for us Europeans, it is truly the ideal climate. For every landscape photographer, a visit to the Saloum Delta National Park would be a must. You can rent a pirogue in Toubakouta, near the border with The Gambia, and get lost in a fascinating maze of over 200 sand and seashell islands. The barren vegetation of the north gives way to lush panoramas of baobab trees and mangroves, inhabited by over 250 species of birds such as pelicans, flamingos, herons, gulls, and royal terns.

From the perspective of photographic equipment, it is generally good to travel light and comfortable.

What lenses and accessories are always in your camera bag, and what advice would you give in this regard to those who are planning a trip to Senegal?

Each person should evaluate how much weight they can carry in their backpack. Personally, I prefer to travel uncomfortably but have more equipment available. If I had to choose only one lens, I would undoubtedly bring a versatile zoom lens, like a 24-70mm f/2.8. But it is also very useful to have a telephoto lens to capture subjects and situations without drawing attention to your presence.

DISCOVERING TERANGA

Diogane, in the Saloum River Delta, approximately 125 kilometers from the capital Dakar, is a village where hard work is the norm. Women collect freshwater mollusks and oysters from the roots of mangroves, while men fish in the river. There is no electricity in the village when the sun is not shining, and the water tanks run dry during long periods of drought. Yet, it is here that I found Teranga, the famous Senegalese hospitality, the reverence and warmth with which guests are welcomed. Africa seems to remind me, like a mantra, that when you have little, you are filled with joy.

Was there a meeting that you remember with particular emotion?

During my trip to Senegal, there was a meeting that I remember with great emotion. I will never forget the children of the village of Diogane, which has a population of 2,000, in the Saloum River Delta.

There is a small school and a clinic, and there is always a need for notebooks and medicines. In this part of Senegal, the predominant ethnic group is not Wolof, like in Dakar and Saint Louis, but Seher. Their kindness and hospitality will always remain within me.

I was able to photograph the fishermen and share their toil, as well as freely play with the children on the streets. At school, the students welcomed me with big smiles and enjoyed having me sit among their desks, pretending to be their teacher. It is this kind of hospitality that warms the heart of those fortunate enough to travel in Africa. In Senegal, they call it Teranga, a form of supportive generosity that makes the stranger feel safe, surrounded by friends.

Andrea Marchegiani collaborates with Domiad Photo Network, the largest national network dedicated to Photography, structured in Web Forums, Blogs, Official Channels on Facebook, Telegram, and Twitter, as well as being spread throughout the territory through the two official delegations of Canon Club Italia and Nikon Club Italia for each Italian region.